When I first saw Rance Jones’ paintings, my mind immediately went to American realist master Clark Hulings (1922-2011). I’ve lived and breathed Hulings for the past few years, in preparation for the monograph I ultimately wrote: Clark Hulings and the Art of Work.Like Hulings, Rance Jones seems drawn to otherness, to people and places that grate against that old chestnut: Paint (or write, or whatever) what you know. What is even more like Hulings is that Jones’ images never strike the viewer as exotic, romantic, like postcards from a trip, or as journalism. Yet even as they avoid the picturesque, they do not seem freighted with ideological intent. Jones’ paintings present humans we do not know—and, perhaps, do not, or rarely, see—in human situations unfamiliar to many of us. In other words, Jones’ works ask to see, indeed, they insist that we see, our common humanity, no matter the cultural backdrop.  Falling, 2020, watercolor on paper, 27 x 36 in.Our common humanity is the bass line beneath Rance Jones: Watercolors, a new exhibition opening at Forum Gallery in New York on March 5 and continuing through April 18. This will be the third solo exhibition for Jones at Forum Gallery. On view will be “more than 20 new watercolors on the theme of Cuba—a subject that has been a focus for the artist since he first visited the island nation in 2018—as well as works depicting the people of Israel and Palestine, as observed by Jones during his visit to the region in April of 2023,” notes the gallery. A new monograph, Rance Jones: Watercolors of Cuba, will accompany the exhibition and on Saturday, March 7, Jones will be on hand to launch the book.

Falling, 2020, watercolor on paper, 27 x 36 in.Our common humanity is the bass line beneath Rance Jones: Watercolors, a new exhibition opening at Forum Gallery in New York on March 5 and continuing through April 18. This will be the third solo exhibition for Jones at Forum Gallery. On view will be “more than 20 new watercolors on the theme of Cuba—a subject that has been a focus for the artist since he first visited the island nation in 2018—as well as works depicting the people of Israel and Palestine, as observed by Jones during his visit to the region in April of 2023,” notes the gallery. A new monograph, Rance Jones: Watercolors of Cuba, will accompany the exhibition and on Saturday, March 7, Jones will be on hand to launch the book.

Intricate Imbalance, 2024, watercolor on paper, 34 x 30 in.

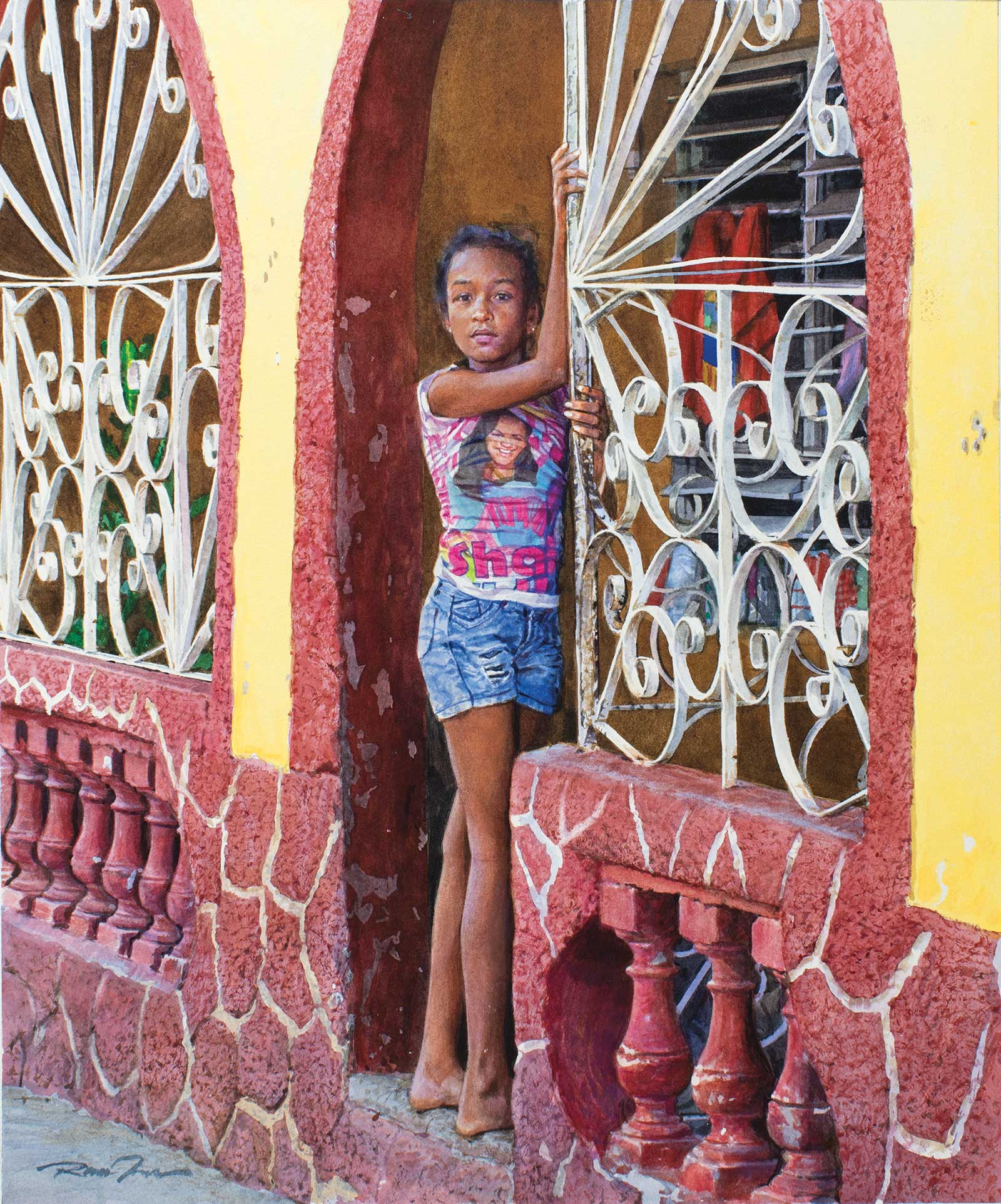

Intricate Imbalance, 2024, watercolor on paper, 34 x 30 in.A native of Lubbock, Texas, Rance Jones moved to New York City in 1991 where he attended the School of Visual Arts and chased an MFA in illustration. For the next 10 years, he worked as an illustrator for, among others, The New York Times and National Review. After making the move from lower Manhattan to Washington Heights, Jones was asked by his church to help organize a children’s ministry in Harlem. His online biography describes what happened next and how it influenced his art: Jones “volunteered with a chemical recovery program where he heard men share raw, heart-breaking stories from violent crime to prostitution for drugs. The artist came to see how difficult it was for children and families, young women and young men to navigate their way through such bleak circumstances…Through these interactions, Rance had to confront prejudice, not only the distrust he encountered but more importantly his own characterizations of the people around him. The struggle to understand and eventually value such a different culture was difficult, at times frustrating but ultimately, an invaluable opportunity to grow.” Jones took this experience back to Texas, where he has since pursued his art on his own terms.

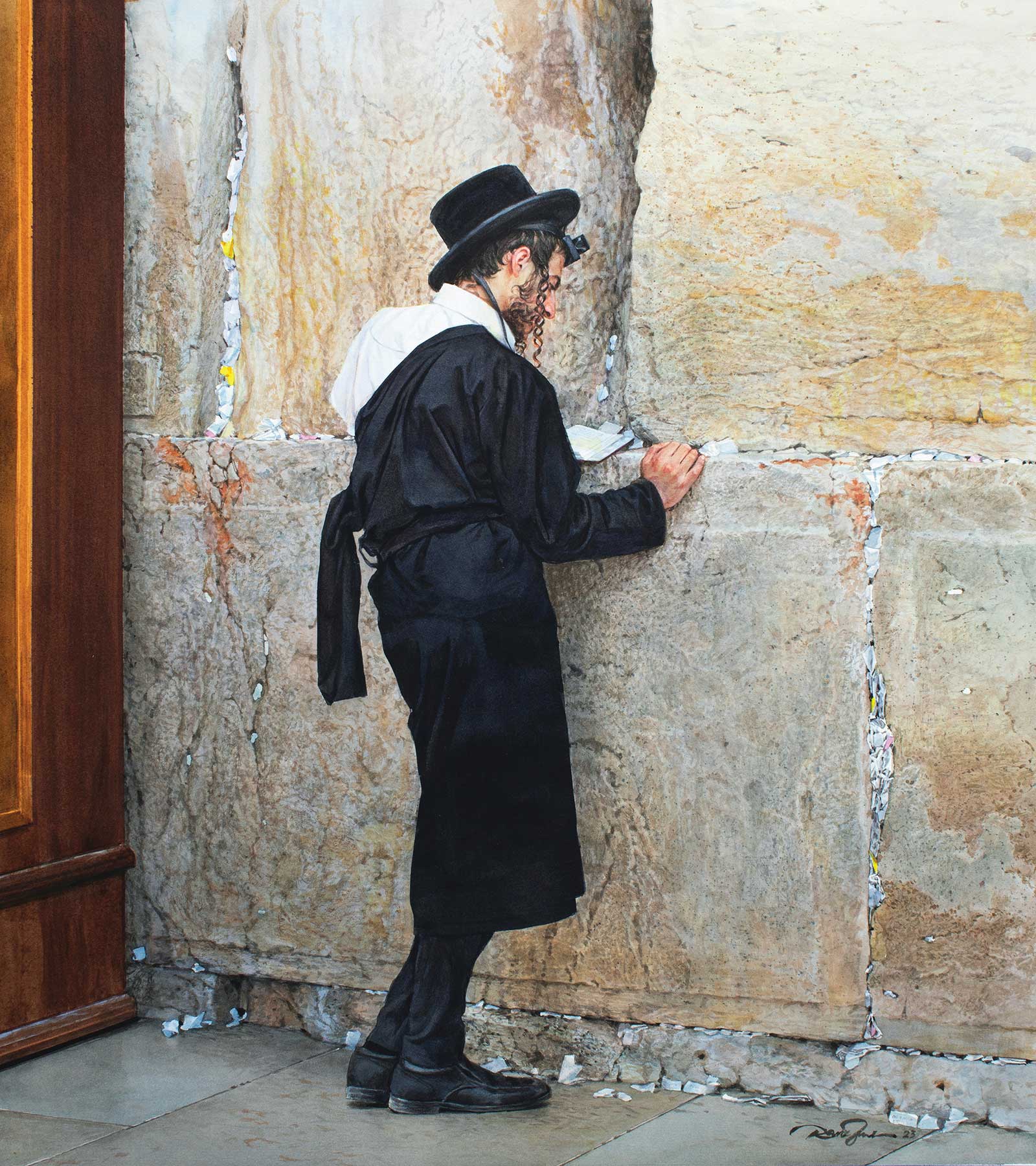

Wall, 2023, watercolor on paper, 25 x 22 in.

Wall, 2023, watercolor on paper, 25 x 22 in.What makes humanist realism—maybe that’s already a term, maybe I just coined it—so difficult and so moving is that it has to tell a story through the sheer suggestion of external form. By its nature, paintings like Jones’ leave a great deal out. Technical challenges like point of view, lighting and the arrangement of shapes on the picture plane, translate into tales that are, at best, half-told. When it works, and Jones makes it work, the viewer fills in the details, becoming a participant in the alchemy that makes a bunch of colors and shapes on a rectangle into a shimmering field of meaning. That Jones does what he does in watercolor, when oil or acrylic would seem more suited to the precision of his forms, makes his work all the more astonishing.

When a writer makes so bold as to say what I just said, I guess it’s time for some for instances, for the proverbial proof in the pudding.

Jaffa Gate, 2023, watercolor on paper, 24 x 21 in.

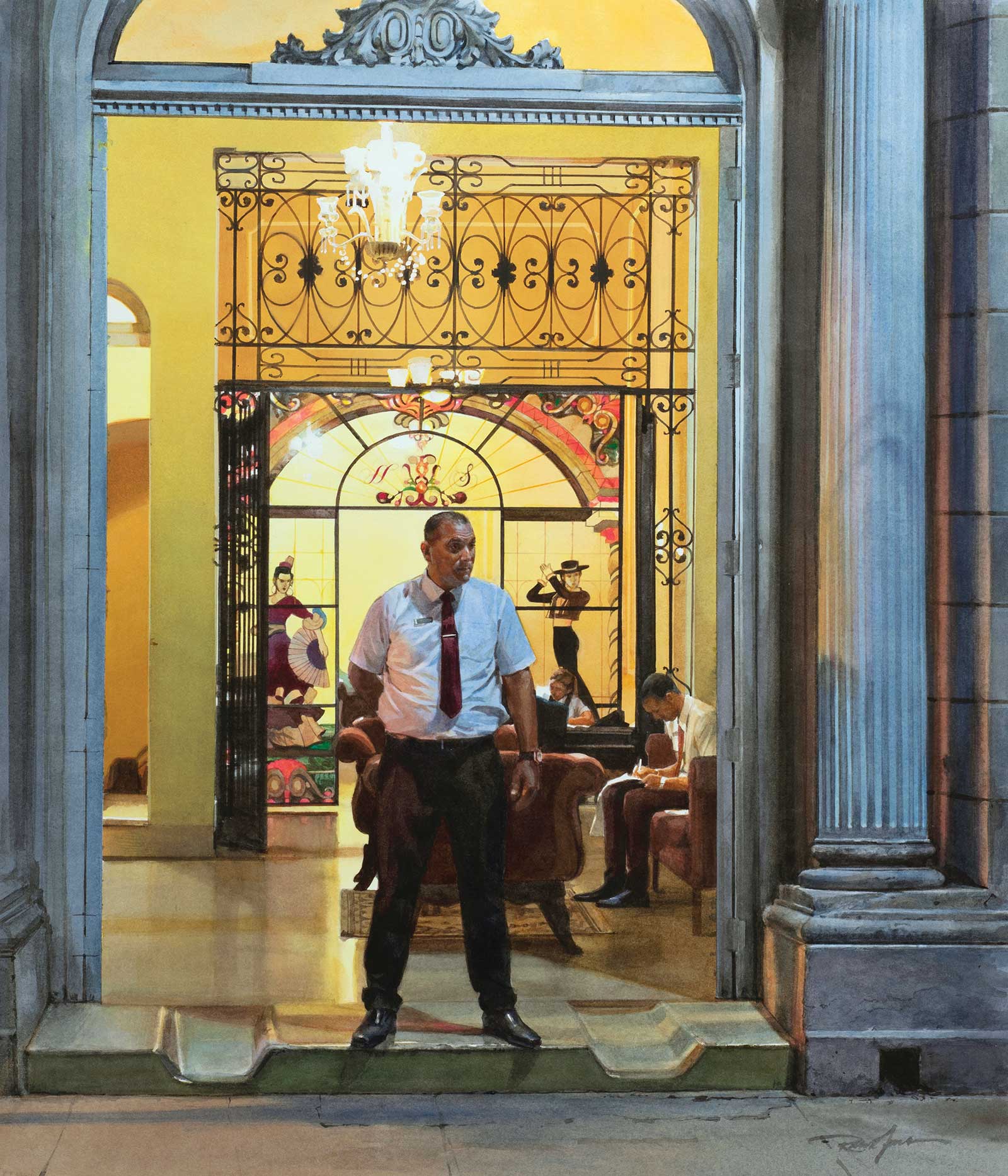

In Night Shift, a painting of Jones’ Cuba, we see a night watchman standing in the doorway of what seems to be a hotel, or an upscale apartment building, or even a private club. But is he just a night watchman? Could he be a guard? A bouncer? Some sort of Havana muscle for the owners of the establishment? Inside, the seated figures seem absorbed in writing, filling out forms, time sheets, applications. They undercut the underworld scenario playing in my mind, as does the simple uniform and the brass name tag on the man’s shirt. But the watchman—let’s call him that—has his right hand behind his back, as if he is holding something. A gun? And we’re back to where we started. Then there are the Spanish dancers in the stained glass, behind the watchman, but, on the picture plane, flanking him. They remind us of the relationship (often fraught) between Spain and Cuba, and suggest a history that informs the architecture and, perhaps, the heritage of the watcher.

Coming and Going, 2024, watercolor on paper,15¼ x 12½ in.

Pink Fins, 2024, watercolor on paper, 13 x 15¾ in.

Blue Bicycle, 2024, watercolor on paper, 14 x 11 in.

It’s exactly the kind of scene we might walk by, or drive by, and spin out into a story, one that breaks down at every turn. Meanings may proliferate and never settle; the image itself remains indelible.

Falling, by contrast, exposes the side of Cuba that has tumbled from colonial splendor and exploitation. The young woman in a student’s uniform and backpack looks down at her cellphone, telling us that this is our time, our now, while nature encroaches on past of the place. Arabesque arches—is this work meant to complement Jones’ work in Israel and Palestine—hearken back to Spain’s Moorish past while the terrazzo floor seems to be crumbling and vanishing under the student’s feet. Vines hang at left and tree trunks jut into the scene at right. The eye moves around the debris and rests time and again on the light coming through the glass above the door—especially the two amethyst panes. The mind wants to see some sort of positive sign in the purple panes, but they aren’t particularly religious so it’s difficult to ascribe any special meaning to them. Then, three workmen’s ropes hang as if from nowhere; one rope dangles beside the young woman. Lifeline? Perhaps. But still, just a rope. If there is hope for the future here, it’s in the young woman, student against the odds, looking at her phone like every other kid.

Shisha, 2025, watercolor on paper, 25 x 21 in.

In the end, all art is political, whatever its maker’s intentions are. The worldwide assault on the arts, on all the arts, whether those arts are ideological or not, proves this. Art is humankind’s greatest invention. Art builds bridges, finds common ground between us, reminds us that we all love, wonder, aspire, create, remember, grieve. That that arts are under assault shows how dangerous they are to any and all who would arrange us in artificial hierarchies that divide us into the worthy and unworthy. It was in a conversation, one I had, quite by accident, with Nobel Prize winning Northern Irish poet Seamus Heaney that taught me this essential lesson. I have written about the encounter in these and other pages more than once, as it seems to need fairly frequent repeating. The short of it is that I had been in Northern Ireland, home of some of my ancestors, not far from his hometown, I had seen the violence of the Troubles firsthand and the dangers of demonizing anyone—neighbors, in this case—as “other,” as “less than.” I challenged Heaney, asking why his art wasn’t more deliberately political. Art is political, he replied, as is culture, simply by virtue of being art. This is why power fears art, why power insists on trying to control art.

Shoelace, 2023, watercolor on paper, 25 x 21 in.

So let me leave it at this. When I look at Jones’ Intricate Imbalance, I see the armed soldiers at upper right, at the top of an ancient stone staircase, chatting amongst themselves, while the girls—girl students again—chat and await a friend who smiles broadly as she descends the stairs to meet them. I wonder whether the soldiers are there to watch or guard the students, maybe both. Which of the characters I created after looking at in Night Shift are they? And what would they have to say to the young student a world away in Falling? So yes, Intricate Imbalance, like all of Rance Jones’ paintings, lies outside a particular politics, it is profoundly political in the small-p sense Seamus Heaney advocated, recalling not just the decades, if not millennia, of tensions in the Middle East, but also the lockdown drills and heavy security at my kids’ schools, and the very real fear that capital P Politics might take them from me. But Rance Jones’ work is also and always about art itself.

Akko, 2023, watercolor on paper, 25 x 22 in.

Consider the architecture, the arches, pillars, tiles and scrollwork that have stood, and still stand, as mute witness and testament to the roiling, rolling moments of humanity and inhumanity. Consider their beauty. Beauty trumps power. Art may never be enough on its own, but without it, what kind of species would we be, what would endure of our hearts and imaginations, what hope would we have? You tell me.

Art is the most profound expression of our uncommon humanity. —

Night Shift, 2020, watercolor on paper, 21 x 18 in.

Rance Jones: Watercolors

March 5- April 18, 2026Forum Gallery

475 Park Avenue, New York, NY 10022

(212) 355-4545, www.forumgallery.com

Powered by Froala Editor