Yes, we must first speak of the sensual pleasures in Alyssa Monks’ bathroom paintings, which raise the pleasing tickle of a voyeur’s thrill to be admitted into a private and protected space, these invitations to see inside the intimate world of women that lies behind locked doors, to see the forbidden body, and bear witness to flesh revealed. Oh yes, there is erotic love on the lips of her young Kiss, a painting of an onanist playing naked in her bath, with frothy soap sliding over her skin and on the cold wet glass, pearly bubbles rhyming with the spray of water on her face and in steam condensed in drops on her slick, and smooth, and creamy skin, all softly shaped to tempt indulgence, to satisfy an instinctive interest in the uncovered and self-pleased body.

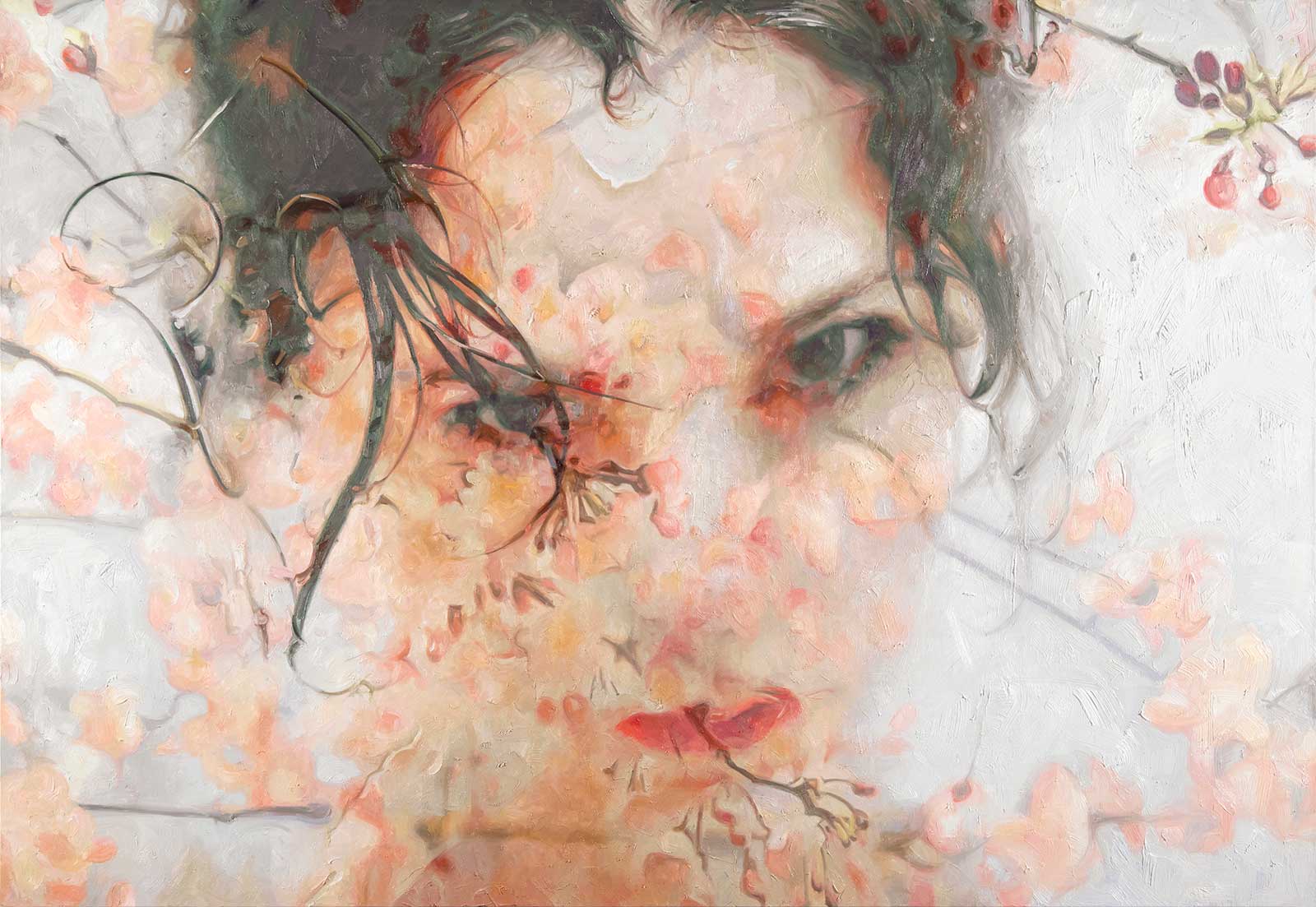

Shapeshifter, 2019, oil on linen, 62 x 90 in. The Seavest Collection.Stop! Yes, in her confrontational contribution to the genre of the nude, Monks deliberately worked on the fine and carnal line dividing erotic exploitation from the eye of psychological self-examination—the soap on the glass emphasizing the picture as a window opening onto a stage, like a theatrical proscenium opened onto a performance. The actor in her play was the woman of the private and interior space, as much as the woman self-consciously displayed and inviting peeping observation. Monks revealed the difficult balancing of self-display and vulnerability experienced by women in all ages—yes, the paintings are erotically alluring, but they also reveal the private body, exposing the complicated mixture of physicality and naïve pleasure that exists with raw suffering behind the locked doors of inner sanctuary.

Shapeshifter, 2019, oil on linen, 62 x 90 in. The Seavest Collection.Stop! Yes, in her confrontational contribution to the genre of the nude, Monks deliberately worked on the fine and carnal line dividing erotic exploitation from the eye of psychological self-examination—the soap on the glass emphasizing the picture as a window opening onto a stage, like a theatrical proscenium opened onto a performance. The actor in her play was the woman of the private and interior space, as much as the woman self-consciously displayed and inviting peeping observation. Monks revealed the difficult balancing of self-display and vulnerability experienced by women in all ages—yes, the paintings are erotically alluring, but they also reveal the private body, exposing the complicated mixture of physicality and naïve pleasure that exists with raw suffering behind the locked doors of inner sanctuary.

Kiss, 2011, oil on linen, 72 x 48 in. Collection of Alan and Nancy Manocherian.

Monks’ shower pictures joined a long canon of wet women painted nude in boudoir scenes. Jan van Eyck’s lost and explicit betrothal panel was created to tempt a wedding; Edouard Manet’s delightfully delicate and domestic bather in Le Tub is a moment and sharing of intimacy as sunshine and morning light brighten the body of a pretty girl, who returns our gaze with calm and friendly confidence; bright Pierre Bonnard’s many psychedelic visions of his wife Marthe soaking in her long tub were deeply founded on domestic familiarity and trust; Lee Price made bath-time food the secret pleasure of her women’s personal space; and Mary Cassatt borrowed the formal delicacy of the ukiyo-e floating world to her distanced bathing. These genre paintings are not alike—some are teasing invitations; some are nakedly lecherous and pornographic pleasures; some are tender expressions of fearless affection; some are revelations of the inner world of a woman’s mind.

All my Desires, 2025, oil on linen, 80 x 80 in.

After her mother died, a grieving Monks was pulled away from herself as the recurring subject of her work—she was still fascinated by the division of inner and outer worlds implied by the glass enclosure of the shower cubicle, but found similar expression in a spiritualist’s separation of worlds before and after death. There was comfort in the ending of the ancient myth of Pandora, who released all the evils of the world when she lifted the lid of the jar she carried to mankind as a false gift from Zeus who sought to punish Prometheus, but hope and anticipation remained inside embodied as Elpis, and Monks painted the daemon as a spirit among the trees, an image of the veil between the worlds of life and death. Hope endured. “I realized at some point I was trying to bring her back,” said Monks, “she loved trees, she loved nature. I looked at it and I would think, ‘she would have loved this.’” The glass was gone, but the threshold remained.

No one Can See Everything, 2023, oil on linen, 47 x 69 in.

Briefly retreating from the fading spaces between the spirit world and materiality, but with her mind still firmly focused in the in-between, she embodied the dryad in Between Here and There, first drawing the foliage of vines onto her model with make-up pens, then painting a representational image of her folded over her knees in the exhausted fetal attitude of supplication. Unusually for Monks, the nude is staged in a bedroom, on pure white sheets, but the bed and the bath are the most private spaces in a home, and the bed is the liminal place where life is conceived and where we die. The bed, where we travel in sleep to the otherworld of dreams and the gods. This dryad’s spirit is at the core of self-examining Monks, that wild tree spirit protected by the ancient dragon that the new man Cadmus killed at Ismene’s pool, spearing her guard to the tree.

Between Here and There, 2022, oil on linen, 43 x 63 in.

Still deeply moved by her mother’s death, but continuing her theme of self-examination, Monks painted herself in the spiritualist mood, like Narcissus peering through floating petals into the reflecting pool, losing her identity among the delicate fragments of flowers and fractured reflections, especially scattered in her No One Can See Everything, and the shattered self in Stay Focused. Now, the formal glass proscenium of the theatre of the shower dissolved into the ethereal separation between life and the mirror.

Critical Mass, 2023, oil on linen, 56 x 56 in. Collection of Leonidas Spyrou.

A second hard loss came when Monks’ brother Mike died three years ago, “…I stopped my life and I went and took care of him,” she says, “He was my best friend, and he asked me to go through his cancer with him—he had a brain tumor.” To exorcise the grip of grief she worked in self-revelation, stripping herself of sorrow, pouring emotion into brush and paint. Ambiguity was always there in those faces pushed up against the glass—were agony or ecstasy expressed in those open, impassioned mouths, and tight-closed eyes? In those paintings sharp pleasure and soft pain met on the subtle edge of slippery eros. All My Desires emerged from the watery work born of her private world of shower scenes and fast condensing steam as Monks turned from love and lust, and license toward rage—a silent scream behind the naked glass in the intimate space of the bathroom. Now, the bathroom was the private space of the “tyled” mind, guarded by the psychic sword, and now we were to become voyeurs to witness the intimacy of private suffering. But as a painting exhibited to the world, this image from behind a locked door became the public face of a private place for pain. If Monks’ crystal cubicle was where the dirt of the world might be washed away in her past paintings, now we were witnesses to revelation as she wept cathartic tears for the cut and loss of her beloved brother, washing deep sorrow within the cleansing stream.

Elpis, 2018, oil on linen, 68 x 86 in. The Bennett Collection.

This second loss was raw. If Kiss was in the tradition of erotic intimacy, All My Desires was entirely of the mind, and recalled the violence of Norman Bates’ insanity in Psycho, and the stripped image of Janet Leigh screaming in her blooded shower. But the silent scream was not the end, and Monks longed for freedom from the pain. She says, “…I’d been struggling with his loss, of course, but I was determined to get through it as quickly as I could, and I was getting frustrated with how long it takes, because it really does take a long time.” She read Henry Scott-Holland’s famous poem, reminding her that “death is nothing at all.” That her brother Mike had simply slipped out of the room, and she recalled his surprising words as he lay dying. “…in the midst of being flooded with all this love from people around him who were reaching out to him—it was Covid, so it was all over Zoom—I watched him getting all this love, and all this attention, and all this sincerity, and everybody was so vulnerable, and he was too, and he felt so loved, and it was really making him feel great, and he grabbed my arm and said, ‘Oh, my God, you’ve got to try this!’” So, desiring the end of grief, she did what he said and let her heart open, choosing to live for love and to love to live. And suddenly food tasted sweeter than before, and sounds and songs were pleasing to her ears, and she discovered fresh enchantments. Banana pie became an obsession, and she indulged in gentle days, and she realized she must now paint what she felt—and what she felt was pleasant luxury. Her lost brother would have loved all the pies! Sweet cream and custard, apple, cherry pies!

Stay Focused, 2023, oil on linen, 36 x 36 in. Collection of Adam Beckerman and Beth Lee.

All My Desires seemed to be returning to her old and accustomed path of play with suds and soap splashed and smoothed indulgently onto the shower door, mixing glycerin and shampoo with pain, and searching for refreshing images of something new, and only finding misery. But now she bought a dozen different kinds of pies and mixed them together with her hands, slathering colored creams onto glass and enjoying accidents of rippled waves, the muddled lights of chroma and canned fruit, painting long swoops, and smooth loops of richly gestured paint from photos of the smears.

Resist, oil on linen, 32 x 32 in. Collection of Lee Dudacek.

She has created half a dozen incomplete canvases of the creamy imagery, and says she is in love with the work. They are not obviously pictures of smeared pie. The new paintings are open to fluid interpretation—enthusiastic admirers who have seen them in their unfinished state have described their experiences to her. She explains, “I’ve had people say they see horses, heaven, they see sex, they see vulvas, they see dogs…” I imagined them as flowers.

Hung Drawing, 2024, charcoal on Bristol, 17 x 24 in. Collection of Steven Kirby.

“They’re abstract moments that are painted realistically,” she says, “what’s interesting to me about them is that you’re not able to define them. What happens is when people look at them then they see things. It’s called pareidolia, where they see shapes they want to recognize, as if the brain wants to identify something there, and I think that’s fascinating, because I don’t see any of that, and nobody sees the same thing...I think it’s very psychological and my work has always been psychological, but this is a whole different level, just playing with different people’s interpretation of abstraction, when they want to see something. But I like the idea of them having to sit there and not know what they’re looking at, their brains struggling to identify it.” In the flow and state of connected consciousness, intuition is often our guide, and though a superficial excess of saccharine may be the lure that leads our response to these delicious paintings, the journey that led to them mixes the sweet and sugared blends of color and whipped cream with just a hint of a stripe of sadness.

Scream III, oil on linen, 24 x 36 in. Collection of Debra Heitmann.

New paintings in progress.

Monks’ recent cake and cream paintings connect her to the lineage of sunny Wayne Thiebaud, whose tasty body of work is a confectionary baker’s display of pleasure, and Will Cotton, whose candy floss and cream paintings wobbled on the edge of exploitation, but enjoyed the same decadent pleasure in sweet sensuality that was once called kitsch by the enemies of sensory experience. All three are concerned with performances, and superficiality, and display, and what is revealed by the protective barriers placed between one person and another. Oh, yes, the canon calls. —

Powered by Froala Editor