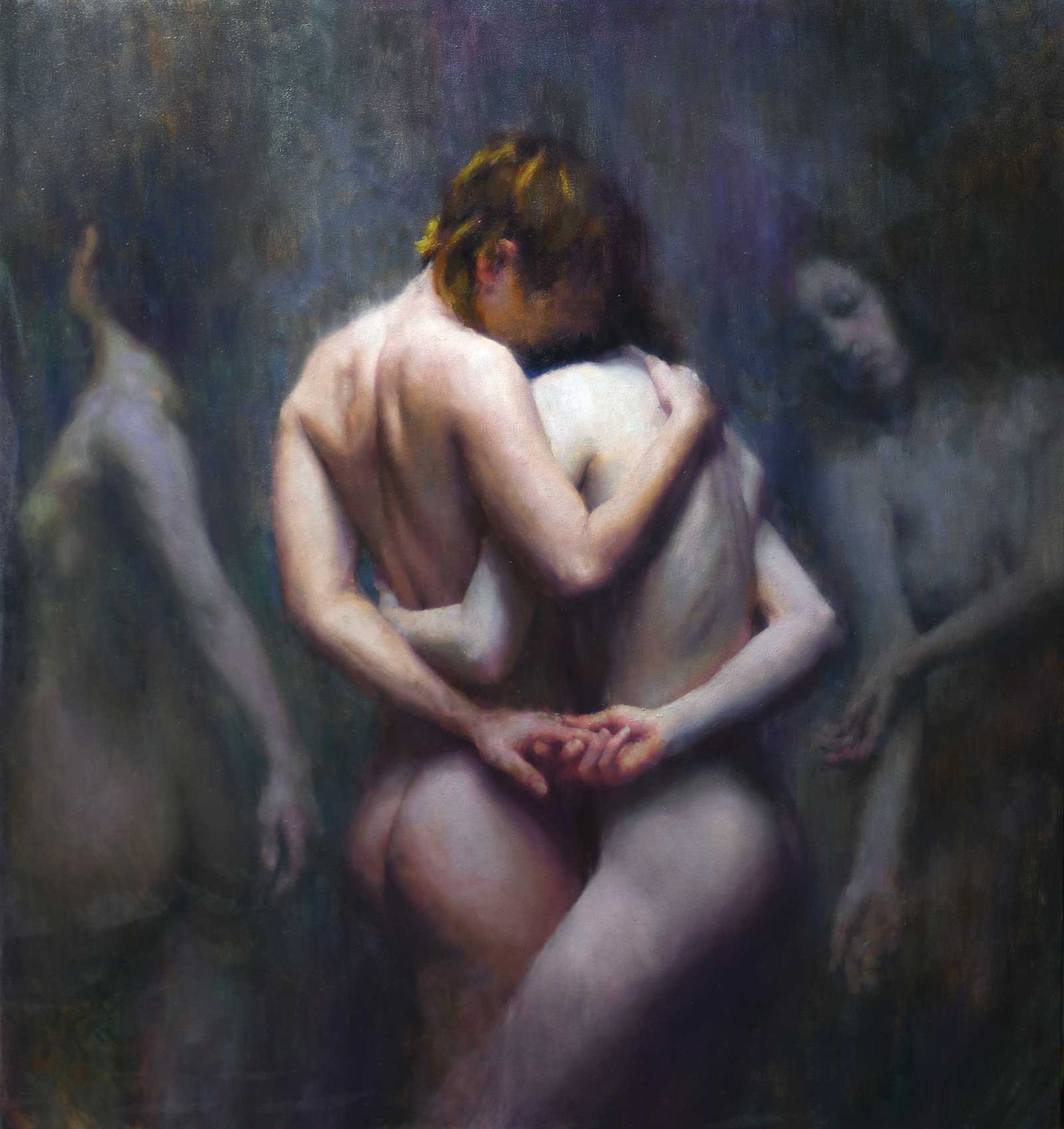

This is love. In Stephen Early’s Come Away With Me,two dancing lovers seen through a subtle and subterranean veil of soft darkness arrive in a glow of light placed carefully to a cue called on a darkened stage, with their entwined hands of grace in a moment of touch in a sensual and naked intimacy. Their arms are concealed behind bodies pressed together in a tight embrace of mutual solitude. As unheard phrases of distant music play, gray figures of other dancers move close behind them, and they are caught in the gesture and delicacy of a private moment of connection, like a scene imagined in a smoky choreography by Damien Jalet, and that clean but soft-edged beam of theatrical light sequesters our couple from these others’ insulated isolation.

Come Away With Me, oil on linen, 28 x 26 in.

Come Away With Me, oil on linen, 28 x 26 in.What a rare and special pose this is! These whispering figures chosen by Early, a connoisseur of the warm language of dance, crafting a discrete dialogue from the soft poetry of the flesh. The ambiguity of the figures and the uncertainty of their heads suggest a world of possibility. This could be any of us found in this delicate moment—when individuality is lost in a miracle of merging souls, the moment of love when the one meets and melds with the other. The touch of their intimate hands is a secret shared. Early says it’s a fleeting moment of “attraction or connection that is not able to happen, so it happens in private. It’s an intense brief encounter,” as the ghostly dancers in the world upstage can’t see the intensity of the intwined fingers hid behind the backs of the faceless lovers.

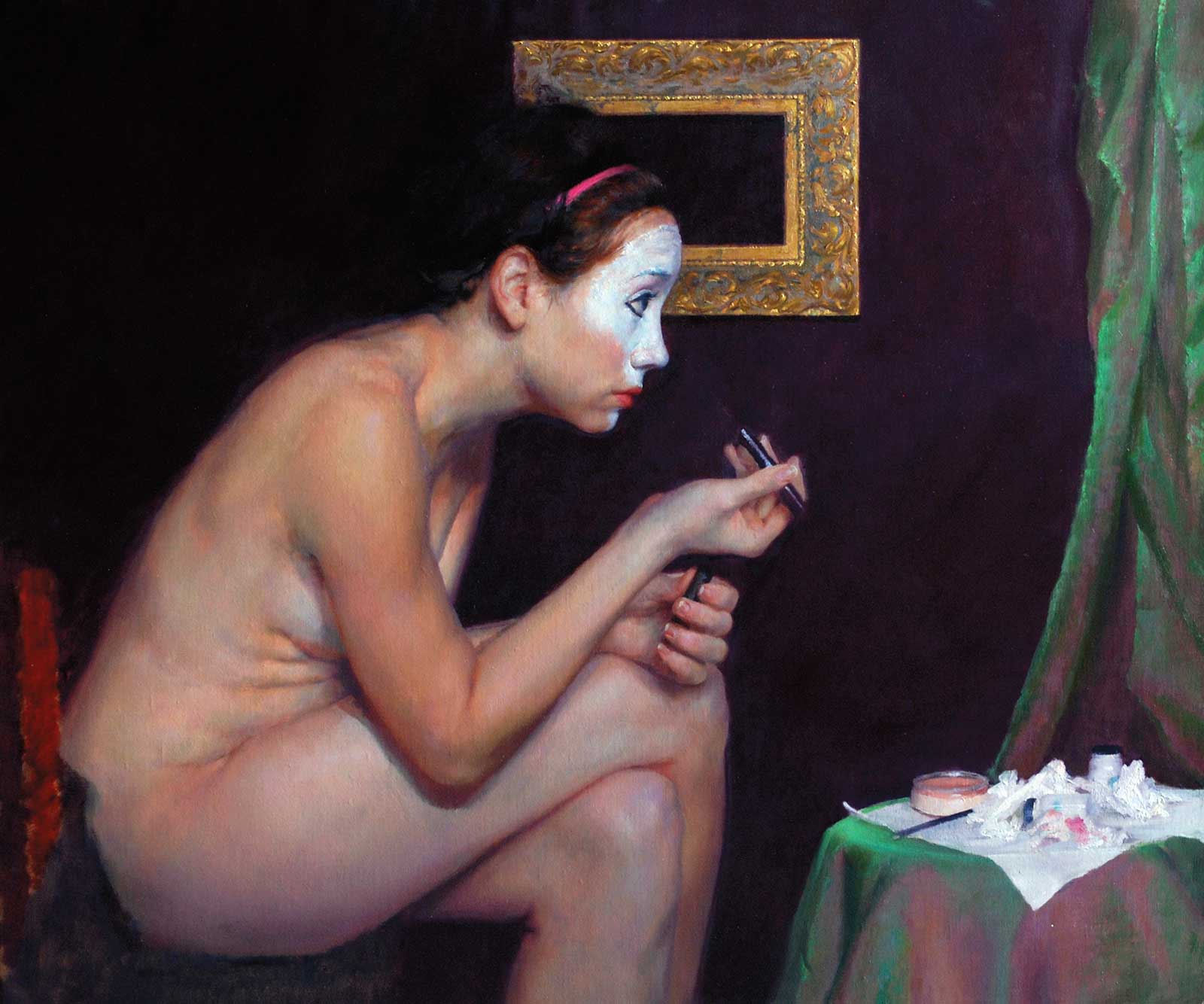

I Wanna be Adored #3, oil on linen, 30 x 36 in.

That fine fourth wall in Early’s paintings runs parallel to the proscenium arch of the theater. His backstage I Wanna be Adored #3, set in the dressing room of a nude performer applying white greasepaint, was a breakthrough for him, but music and poetry are at the beginning, middle and end of Early’s process. He found inspiration in Sara Teasdale’s short verses for the painting Two Minds, where the lovers’ arms are discovered braided across a transparent phthalo break of watery depth, above in crisp clarity and mass, and below in veiled atmospheres of uncertainty and occlusion.

Your mind and mine are such great lovers they

Have freed themselves from cautious human clay,

And on wild clouds of thought, naked together

They ride above us in extreme delight;

We see them, we look up with a lone envy

And watch them in their zone of crystal weather

That changes not for winter or the night.

But poetry isn’t Early’s most important muse. “Most of my inspiration comes from music,” he explains, “listening to music, how it makes me feel…It’s not totally dependent on the lyrics; it’s got more to do with the music itself. It’s a constant source of inspiration, how it makes me feel. That starts the process of exploring those feelings, or it might be right in line with what I’m looking for in a painting. Oftentimes, I’ll take the same music and play it at the photo shoot. It’s really interesting when it all syncs up and the model gets in touch with the music, and you can see it starting to effect how the model moves.” Like the brilliant sculptor Richard MacDonald, who was featured in the January issue of this magazine, Early works closely with his models, starting from an idea—sometimes sketched—or a mood, giving direction as he uncovers moments of significance with them. He says, “I talk to the models about the general idea, the general concept, the general feeling. There’s a lot of movement. I don’t establish a pose.” Like a great choreographer, he is a connoisseur of the subtle instants of lucidity he discovers as he guides his dancers.

Lucid dream #2, oil on linen, 9 x 18 in.

He prefers music that is played on modern electronic instruments but ignores the formulas of conventional rock and roll. He likes the delicacy and dream of soundscapes by post-rock bands, like the mellow shoe-gazers, Elbow, the abstract albums of Talk Talk, and the transcendent Icelanders Sigur Rós. As well as singing in his native tongue, the Sigur Rós vocalist Jónsi Birgisson often sings in the words of a vivid and invented language he calls Vonlenska, creating ecstatic streams of lyrics in the language of the seraphim, backed by inspiring chords played with a cello bow on an electric guitar, and rousing rhythms like an electrified heavenly choir.

Birgisson sings, and Early speaks through pigment and paint. And as the poetry and rising dialogue of his work is formed in the inspired tongues of sable and synthetic brushes, and sung in the songs of his studio’s Icelandic angels, his grammar and syntax emerge from the flow of his abandonment to inspiration. He scrapes lead over linen and finds figures in the knifed textures, as he slips glazed color over grisaille and opaque hues. Early speaks the Corinthian language of love.

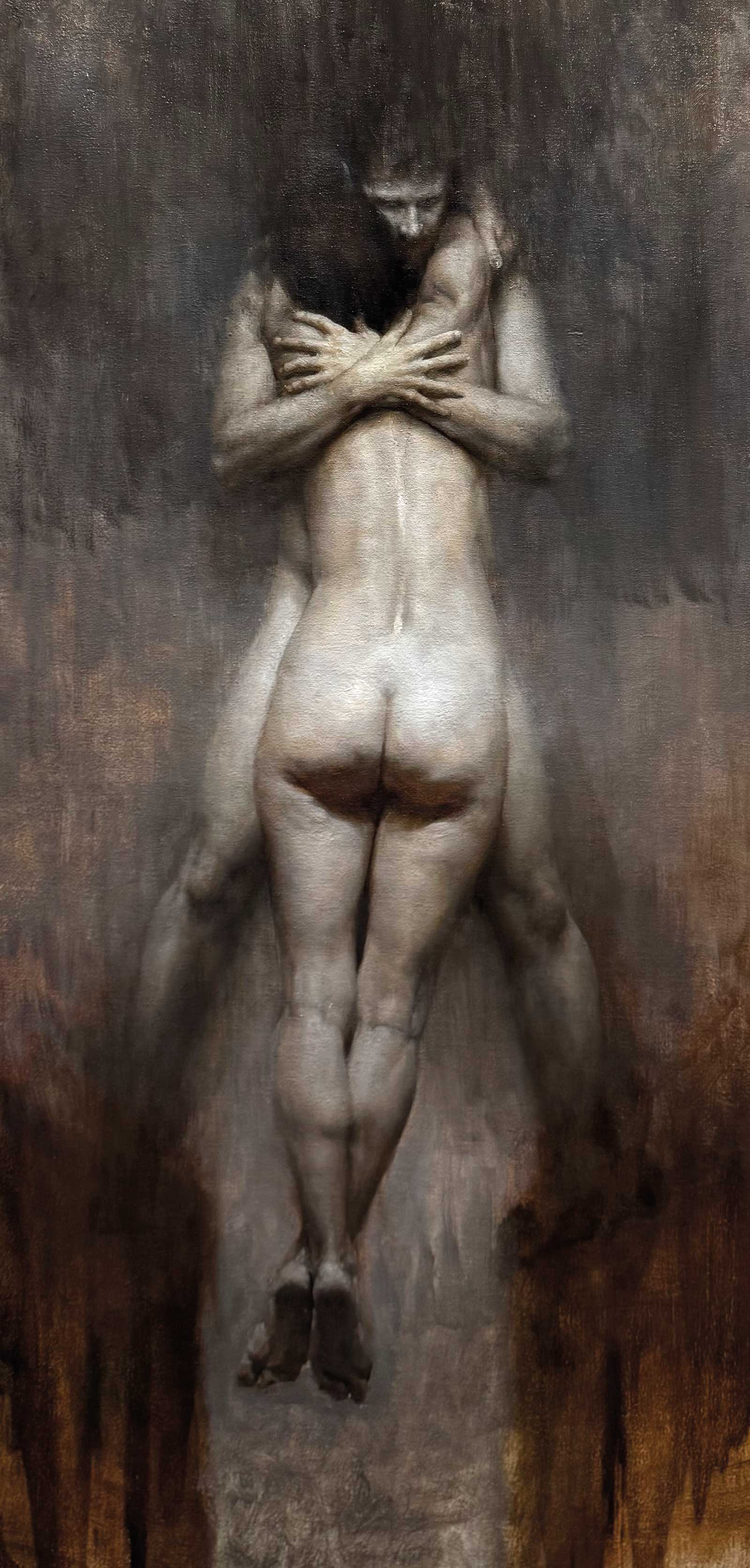

Two Minds #2, oil on linen, 22 x 21 in.

He was an illustrator before he met Nelson Shanks, the formative maestro of Studio Incamminati, who changed the course of his creative life by encouraging him to tread a different path toward quality. Although Early was already an exceptionally observant figurative artist, he was unhappy with the effect the formulaic preparatory processes of commercial art had on his practice. “It wasn’t very creative,” he says, “By the time I was actually painting, it had been drawn and re-drawn and transferred on, then drawn again…I wasn’t able to break out of that once I had that rigid drawing.

The Weight of your Absence, oil on linen, 26 x 16 in.

When I met Nelson and started studying with him, he showed me the importance of abstraction, especially in the early stages; a simplification and abstraction, blocking things in and simplifying all the complexity of the figure and the muscles and thinking of the shapes of the design of light and shadow and the beautiful shapes that happened in the poses that had nothing to do with the detail of the form. So, that’s how I start everything.” He attributes his own mastery of the life that seems to be present in the flesh of his figures to studying Shanks at work, commenting that in some of his mentor’s paintings he felt he could see the blood of life flowing beneath the skin. Early says Shanks showed him he wasn’t looking hard enough or deeply enough. “He opened my eyes to seeing in a more profound way,” he says.

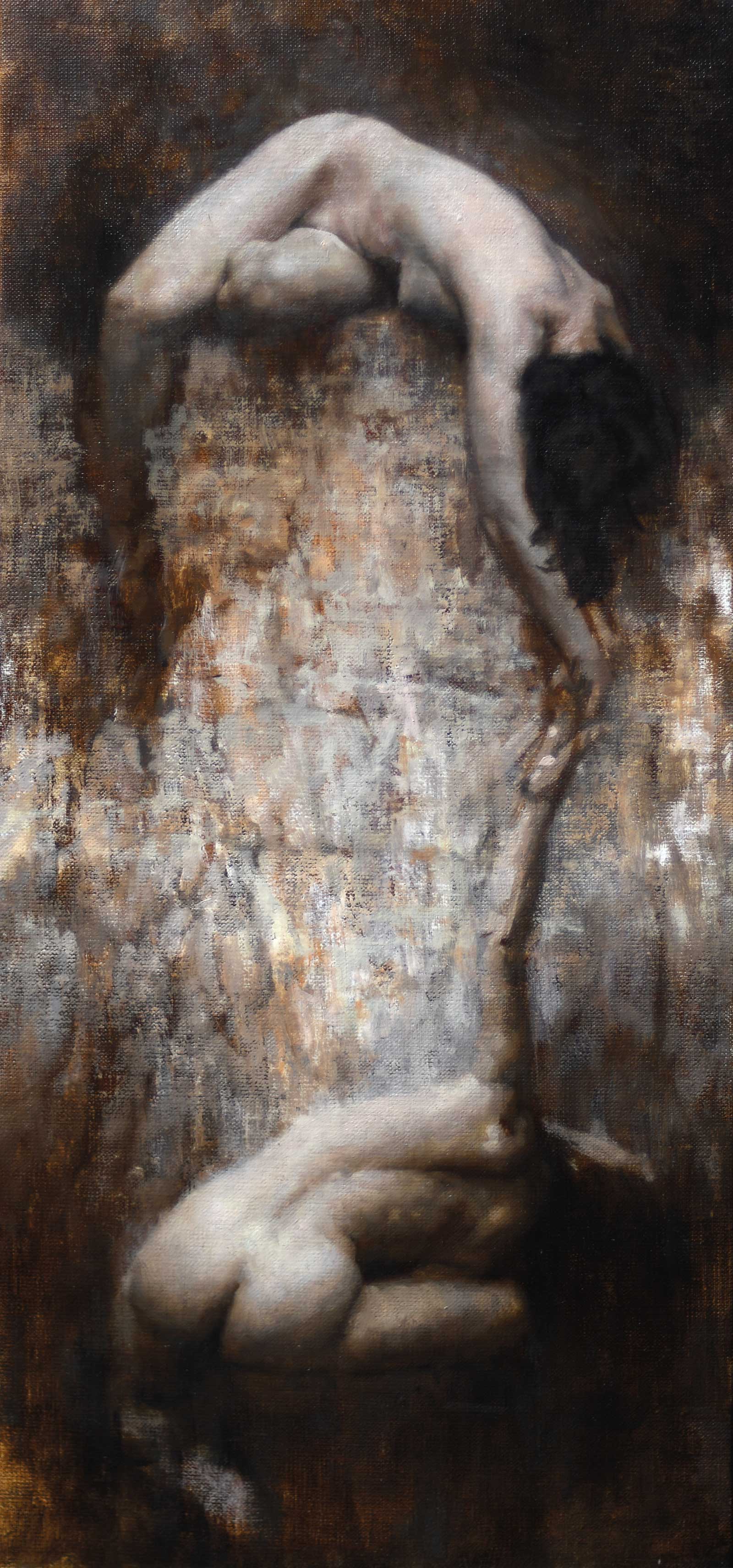

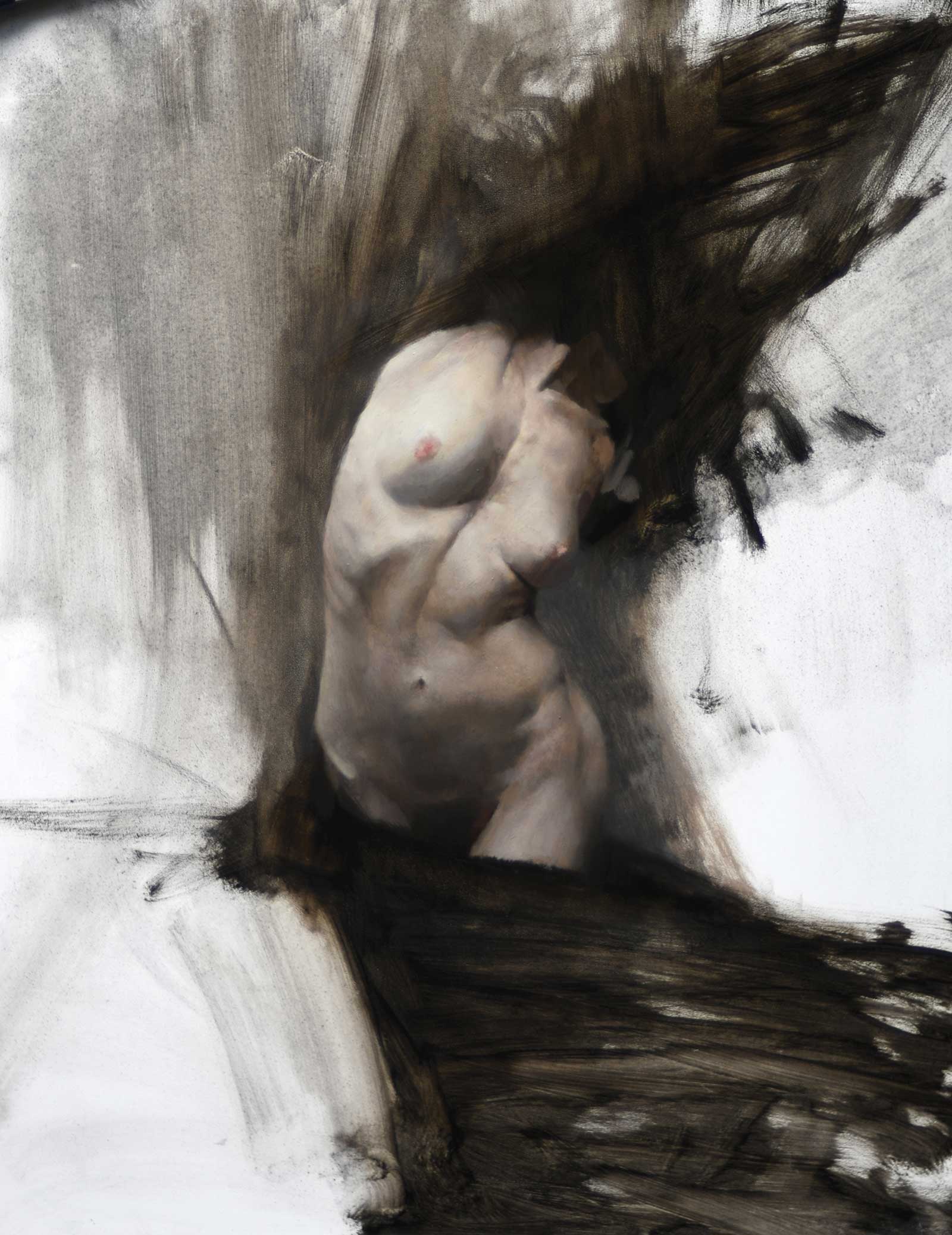

Untitled, oil on linen, 15 x 8 in.

Now he paints more like a sculptor, pulling primal figures from Promethean clay. Like MacDonald, he hunts for moments of elevated spirit within the elemental earth of first beginnings. “I see the form and I build it,” he explains, “I create these very simplified masses and then I carve into it. Taking the paint and applying it as if I’m either adding clay or taking it away…I feel like the most interesting outcomes for me are when you have a balance of abstraction and clarity of form.” Here, in an Orphic but untitled painting, a tragic figure reaches down to find the upstretched hand of her eternally trapped and mirrored other. There is hope for these abraded figures—emerging from the scraped strata of blackened ground and chalk and ashen white, ascending and descending from the subtle blends of color concealed in raw and burnt umbers born of earth and fire. It is the treasured chance of contact between two minds, a chance to find and touch the soul of another. “That theme of a connection above, or taking place somewhere else,” Early says, “a suggestion of some kind of atmosphere balanced out with a little segment of reality or form. Obviously, I love the figure. It is my vocabulary…Anything I want to say, I can say through the figure. I love form. I love the feel. The anatomy. That is my human connection, my humanity. I need some presence of that in a painting someplace, somewhere. So, I’m always seeking that balance and I don’t know the balance until I see it…I need that instead of everything being atmospheric and everything being vague or veiled, someplace somewhere there has to be a solid mass of humanity, otherwise I get lost in the environment.”

Grace, oil on linen, 58 x 36 in.

Early balances his transcendent figures against gravity, floating them above the earthly attraction that would submerge them in the thickening of weight, like water freezing in the white winter. His The Weight of Your Absence was inspired by the poem by Pablo Neruda from a little book gifted to him by a friend.

I crave you as the earth craves rain,

As the sea yearns for the moon’s pull,

Your absence, a wound that bleeds silence,

Each drop echoing the hollow of my heart.

You are the sun that burns my skin,

The wind that tangles my breath.

Even in your stillness, you move me,

Even in your distance, you are near.

I have tasted the salt of longing,

Felt its bitter weight on my tongue.

Yet still, I call your name in the night,

A prayer flung into the void.

Let the stars fall if they must,

Let the rivers forget their paths.

But do not let me forget your hands,

How they held the universe in their touch.

You are not a memory,

You are the pulse of the earth beneath my feet.

A song the waves hum endlessly,

A flame that refuses to die.

In the painting, the strength of the love shared by the man and the woman conspires to find balance between their figures as the woman is tugged toward the underworld. Look at his hands, spread like open wings on her strong back. Look at the power of her trust. The tower of his strength and their faith in each other suspends them against the eternal gravity of loss for a moment, to share briefly in the gift of connection before inevitable time takes her from him. This is love.

Wild is the Wind #2, oil on panel, 18 x 14 in.

Recently, Early has been intrigued by women in water finding true suspension. He jumped at an unusual opportunity when his model, Grace, asked if he wanted to paint her while she was six months pregnant. She knew a secluded swimming hole near her home, and there, Early photographed preliminary studies of her floating weightless in the deep water—a nude and red-haired Ophelia for the present. If The Weight of your Absence was a tragic song of lost love at the end of life, Grace is a painting of the enduring love that is the true gift of being, the lasting love between mother and child, the only love that surpasses death. —

Powered by Froala Editor