Back in the early ’80s, Sally Strand was garnering a lot buzz for a novel multi-media style that involved applying pastels over watercolor underpaintings on traditional watercolor paper. The Colorado native had recently arrived in New York City where, with the courage of naivete, she marched up to the brownstone where painter Burt Silverman lived, knocked on his door, and asked to study with him.

Strand had been living in Chicago prior to moving to New York. She landed there after spending two of her college years traveling through Europe with the nonprofit musical troupe Up with People (which included a performance at the 1972 Olympics in Munich, Germany), first as a member, then as an administrator. Having grown up largely in the mountains of Evergreen, Colorado, the tour exposed Strand to a dizzying array of new visual stimuli, reigniting a life-long affinity for creativity.

Above and Beyond, 2024, pastel on paper, 18 x 24"

“I was taking in so much as a young person,” says Strand. “I remember being in Germany and seeing immigrants walking outside along the train tracks, carrying big boxes, and I pulled out a piece of paper and started drawing. It was my way of trying to process the world around me…I came from a small town. Some people would write; I started to draw.”In Chicago, Strand was working as a secretary and trying to figure out what to do with her life. She applied the research skills she had picked up abroad, pulled out a phone book and opened to the A’s. The first entry she saw was the American Academy of Art.

“So, I went and took a class and thought, ‘This is who I am. And this is important.’” Still very green, she experimented with photography; she read books about Michelangelo and Van Gogh. She ate her lunch at the Art Institute of Chicago everyday, marveling at the works by the Old Masters. “I began to understand the mind of an artist and that I was very visual in my response to the world,” she says. “It was touching something very deep inside of me that I couldn’t really explain. Some people are more attuned to their ears, so they’re drawn to sound and music. For me, it’s through my eyes.”

Shower Door, 2022, pastel on paper, 20 x 15"

Like many realist painters in the ’70s, finding observation-based classical training was nearly impossible. So, eventually, Strand packed up her watercolors and headed to New York. There, taking classes at the Art Students League of New York, she was introduced to artists like Silverman and Harvey Dinnerstein, renegades in a time when realism was regarded as passé, and the conceptual and abstract reigned supreme.

Eggs Underwater, 1991, pastel on paper, 36 x 48½"

Silverman took Strand in even though she had no money to pay him (a debt she repaid later) and let her sit in on his sessions, which were less like classes and more an opportunity to watch him and the other students work, while Silverman philosophized with the group.

“I didn’t understand art history,” says Strand. “I just wanted to draw, and I needed somehow to portray life. I was obsessed with watching people. Now I know that is a whole legacy in art history—painting day-to-day life. [Burt and Harvey], they were painting the everyman. The laborers. But it was more than just a depiction, I felt something about the people when I looked at their work. Now I understood that I was also interested in portraying themes of life—work, labor, leisure. I was always sitting on a park bench or watching the people around me on the bus. I was interested in their lives and what were they like.”

Kari, 2013, pastel, 18 x 12”

One day, back in her little Manhattan apartment, Strand noticed the sunlight glancing off a bowl of eggs sitting on her windowsill and decided to paint them. She was dissatisfied with her ability to capture what she saw in watercolor, a medium that had been growing stale for her, for some time.

“Frustrated, I pulled out an old hand-me-down set of pastels and started scribbling over it on the watercolor paper,” she says, adding that, back then, pastels were considered an insignificant medium typically used by students (despite the fact that Degas, William Merritt Chase and Mary Cassatt are just a few historic artists who worked in the medium). Off and running, she started laying pastels over her watercolors in a cross-hatching pattern. The texture of the watercolor paper created an interesting look that many hadn’t been seen before.

Poolside, White Hat, 2007, pastel, 12 x 9"

“I was trying to capture light and I cross-hatched to make colors that I didn’t have,” she explains. “Now you have thousands, but it was an amazing learning experience”

Seriously engaged with her art-making, Strand all but sequestered herself in her apartment. “I sat by the window for three months, painting at the same time every day,” she says. “I’d go to the fridge and pull out natural things—eggs, apples, oranges—and I sat there and learned everything in those three months. I observed and observed. I used my eyes for the first time. Rather than theories, I thought about what the light was doing, the shapes it created, the shadows.”

Window, 2013, pastel, 24 x 34"

“It was a very important time,” Strand continues. It’s something she has tried to instill in the students she has taught over the years. “‘Go in and close the door. Learn how to use your eyes.’ I had very few materials…I figured I would mix the colors on the paper. That was unusual too. I really had to learn about color—what two sticks will mix to create that? Now, [pastelists] already have all the colors in their box made for them. I learned how to see and how to push materials when I didn’t have them. The technique was secondary to what I needed to say. If you know what you’re trying to achieve, you can make the materials do it.”

Although the world of pastels has exploded since Strand’s early days, with nearly infinite pre-made colors and just as many paper options, and is much more regarded as a serious medium, it is still is somewhat misunderstood. What struck me about Strand’s work was it blew open my limited perception of pastels as largely a medium for landscapes—lavender fields, seascapes and scenes that lend themselves to the Easter-egg color palette we associate with the word pastel.

Men in White #4, 1988, pastel, 41½ x 28"

I was particularly drawn in by Strand’s 2020 painting Journey, not only as an impressive work of figurative realism that demonstrates what pastels are capable of in the most skillful of hands, but also because of the peaceful poignancy the piece exudes. It’s a picture of Strand’s son, who had taken a year off to travel between jobs and invited his mom to meet him in Hawaii for her birthday.

“I turned my head, and the light was coming up from our feet,” Strand recounts. “The sun was very low, that’s why there are those unusual shadows…the little shaft of light over his shoulder, those beautiful kisses of light. I looked over and it just touched me. I was thinking about his whole life and where he would go next and what he will achieve, and where his heart is. I saw that he was in the prime of his life, in a moment of private revery.”

Strand took out her iPhone and took some photos and built a painting around it, making up the sky, the clouds, to create a kind of dreamland, but also to portray the moment as it was being lived. It’s illustrative of the kind of scenes Strand is compelled to paint.

“I’m kind of interested in painting things that are overlooked,” she says. “There are so many unique moments that happen between things. I’m more interested in a person stepping off the step, than when they’re on the step or have already stepped off the step. It’s that moment in between. Moments like seeing my son there…familiar but special to life, and filled with beauty and wonder.”

Journey, 2020, pastel on paper, 19 x 25"

The girl running in Above and Beyond, 2024, was also glimpsed on the beach that day. Strand plucked her out of that landscape and set her in a completely new environment, informed by memories of Strand’s time growing in the West and its wide-open skies.

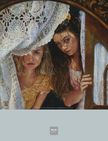

Window is another deeply personal piece and a stunning work of realism. Painted in 2013, it depicts Strand’s mother at age 87. “She was a widow and it was time to move her out of her condo and studio,” says Strand, explaining that her mother was also an artist. “It was a very sad time. I stepped into the kitchen watching her almost saying goodbye to her home. I put my own painting in the painting to represent my connection to my mother.”

After completely rendering out the piece, Strand took a deep breath and did one big smear across the watercolor paper, hoping it would achieve the drip effect she wanted. It did.

A Present Matter, 2021, pastel on paper, 11 x 14"

In 1984 Strand moved to Laguna Beach, California (and still lives nearby in Capistrano Beach), because her friends suggested she submit her work into the Festival of Arts of Laguna Beach, where a prerequisite for entry is living in Orange County. She presented a series of paintings inspired by a trip to China, which had just opened its doors to tourism. They sold out and, that first year, she was asked to create a piece to be enacted in Pageant of the Masters. Gallery representation in New York and Scottsdale, Arizona, followed.

Today, at 70, and having recently given up a rigorous teaching schedule after 40 years, Strand finds herself in another time of transition, confronting the realities of aging and what is coming next in terms of her work.

Essay, 2019, pastel on paper, 12 x 9"

“Something is changing, but my world has always been perceptual,” says Strand. “We’re coming from somewhere; we don’t know where…memories, feelings that we’re pulling out of the skies. It’s kind of exciting and frightening, but every stage of my career has been like that…I’d get to a stage where I thought it was over and then I’d push through it and something else would come in. It’s just the pressing through that’s an uncomfortable place to be because you can’t yet see what it’s going to be.” —

Powered by Froala Editor