Orion magazine assembled a group of writers and artists to write about the influence of the author and essayist Barry Lopez in their lives. The collection was published in January 2021, after the writer’s death the preceding December.

Maine painter Alan Magee wrote, “Barry and I have known each other for thirty-four years. That long friendship would not have come about except for a chain of unlikely events that began in 1982, when I pulled an unadorned paperback called Winter Countfrom the shelf of a bookshop in Santa Barbara. I hadn’t heard of its author, Barry Holsten Lopez, and what drew me to the book’s gray, slender spine remains a mystery to me. Reading the stories back in my hotel room, I was awestruck by their understated power and the precision of the prose. I felt as if I were in conversation with another painter—one who had concluded, as I had, that art begins with our capacity and willingness to observe.”

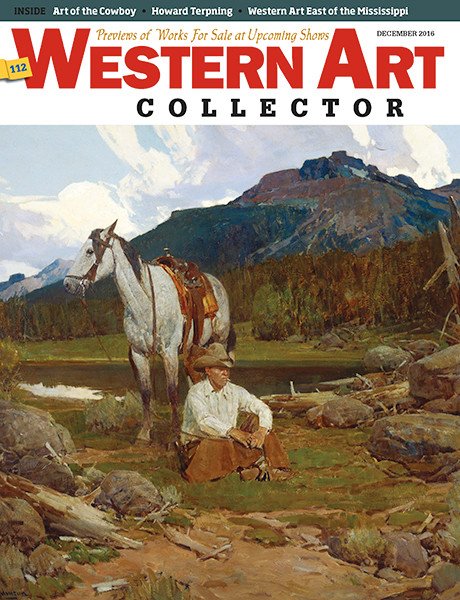

Chord, 2015, acrylic on canvas, 36 x 44 in. Courtesy Winfield Gallery, Carmel, CA; and Forum Gallery, New York, NY. © 2015 Alan Magee

His essay reminded me of a quote by the great physicist Isaac Newton: “I do not know what I may appear to the world, but to myself I seem to have been only like a boy playing on the sea-shore, and diverting myself in now and then finding a smoother pebble or a prettier shell than ordinary, whilst the great ocean of truth lay all undiscovered before me.”

Magee’s powers of observation bolstered a career as an award-winning editorial and book illustrator, producing covers for books by Saul Bellow, Bernard Malamud, John Irving, Henry Miller, Agatha Christie and Graham Greene, among others. However, the demands of the New York publishing world began to infringe on his growing desire to be a painter.

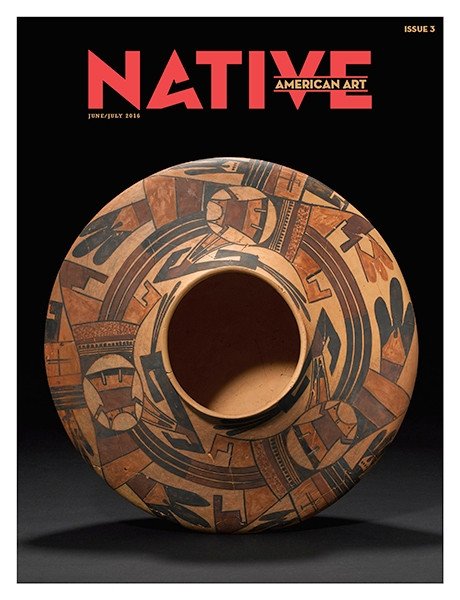

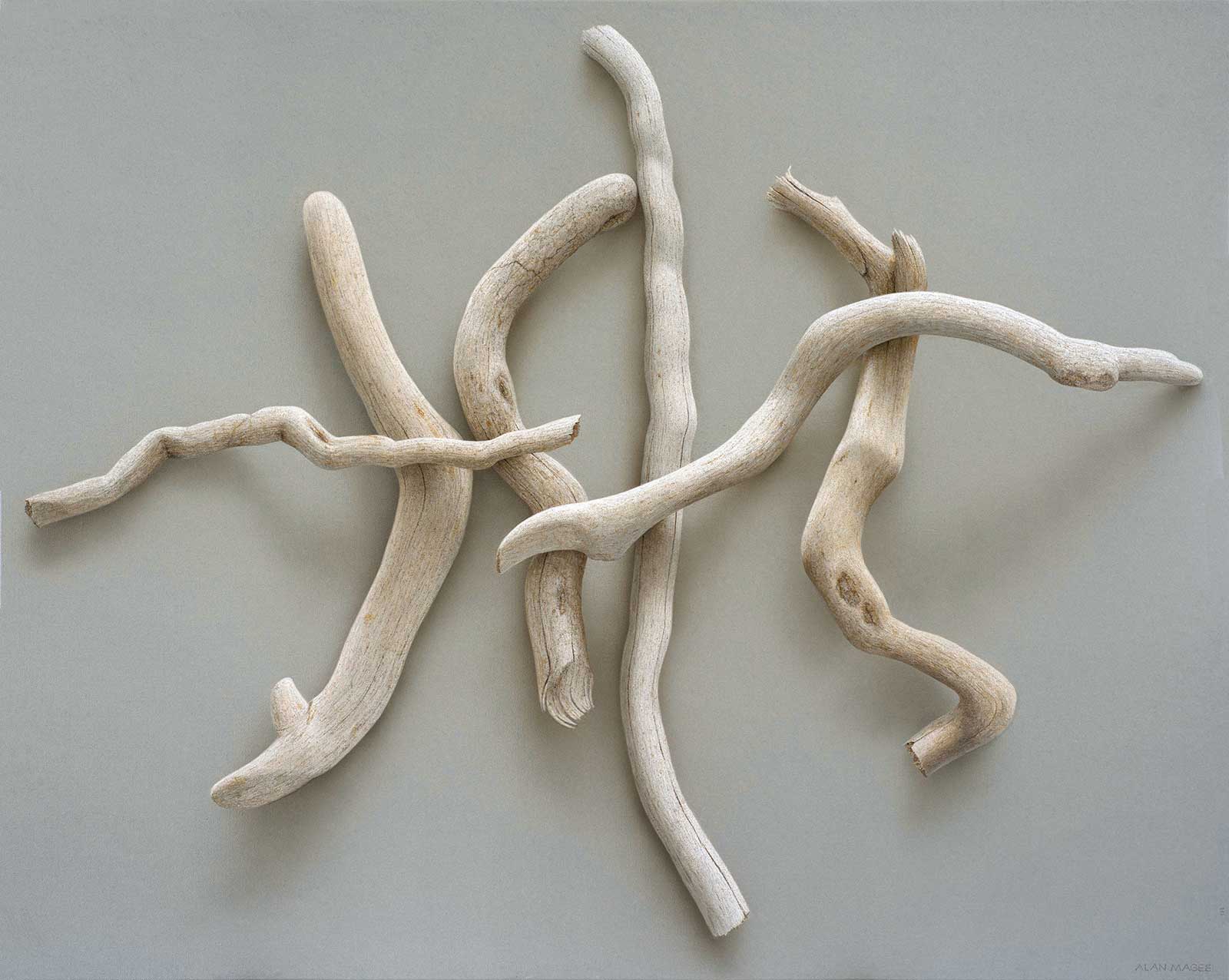

Motet, 2019, acrylic on canvas, 46 x 58 in. Courtesy Winfield Gallery, Carmel, CA; and Forum Gallery, New York, NY. © 2019 Alan Magee

He and his wife, Monika, moved to Camden, Maine, in 1976. Their first summer, a young friend took them to Pemaquid Point about an hour’s drive south along the coast. “The beauty of the place stunned me,” he recalls. He found the sea there “a turmoil in slow motion—the action of water moving stones over and against each other to create these incredible sculptural forms…Those stones and the paintings I made of them became a bridge from my life as a New York illustrator to a new beginning as a painter. The stones at Pemaquid are not only profoundly beautiful, but also suggestive of our place as humans in the vastness of time and space. Painting them gave me the time to consider and absorb their message.

“When a new symbol or a new image appears in your life, at first it isn’t possible to understand what it means or what it’s going to mean. The beauty of it kind of assaults you and it hits you with a walloping force and you realize you’re going to have to attend to it.”

Lopez said of his friend, “Alan wants you to be attentive to the world around you, and being attentive to the world around you means you can’t just stare at what is conventionally beautiful—you must look at the whole panorama.”

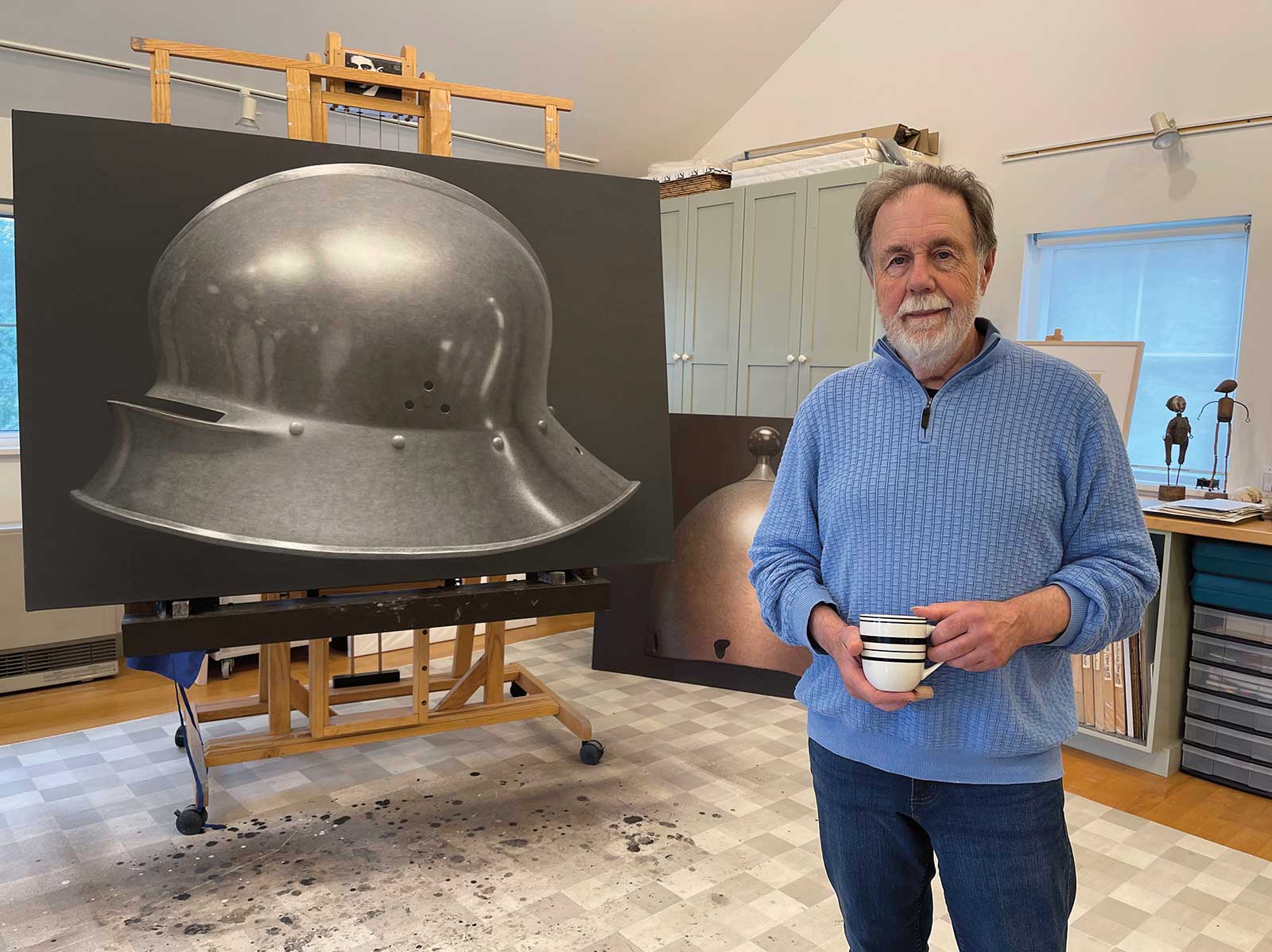

Alan Magee in his studio with the paintings Helmet XII, © 2021, on the easel, and Helmet XIV, © 2021, behind. Photo © 2025 Monika Magee.

The whole panorama included “several trips to the Neolithic sites in the British Isles, for example, [that] brought a new sensibility and compositional structure to my paintings of stones,” Magee shares.

The dolmens and stone circles of Ireland have always attracted me. When we spoke, I told him I sometimes wondered if the stone circles, rather than having astronomical associations, were made simply because their builders thought they were beautiful or possessed what Magee calls a “spiritual resonance.”

After Lopez was diagnosed with cancer, he told Magee about a therapy session in which he and other patients sat in a circle and moved to the center to speak. His painting Surround (For Barry), 2015, is a circle of sedimentary and igneous rocks that bear the marks of their being formed by pressure or having once been molten, broken over time and formed into unique shapes by the ocean just as we are formed by the miracles and vicissitudes of life. He and Lopez gathered driftwood on the coast of Oregon. The sinuous shapes hold the story of the trees’ growth, buffeted by the wind, their branches polished and bleached by the sea and the sun. His nearly 4 by 5-foot painting Motet,2019, is a composition of pieces they gathered.

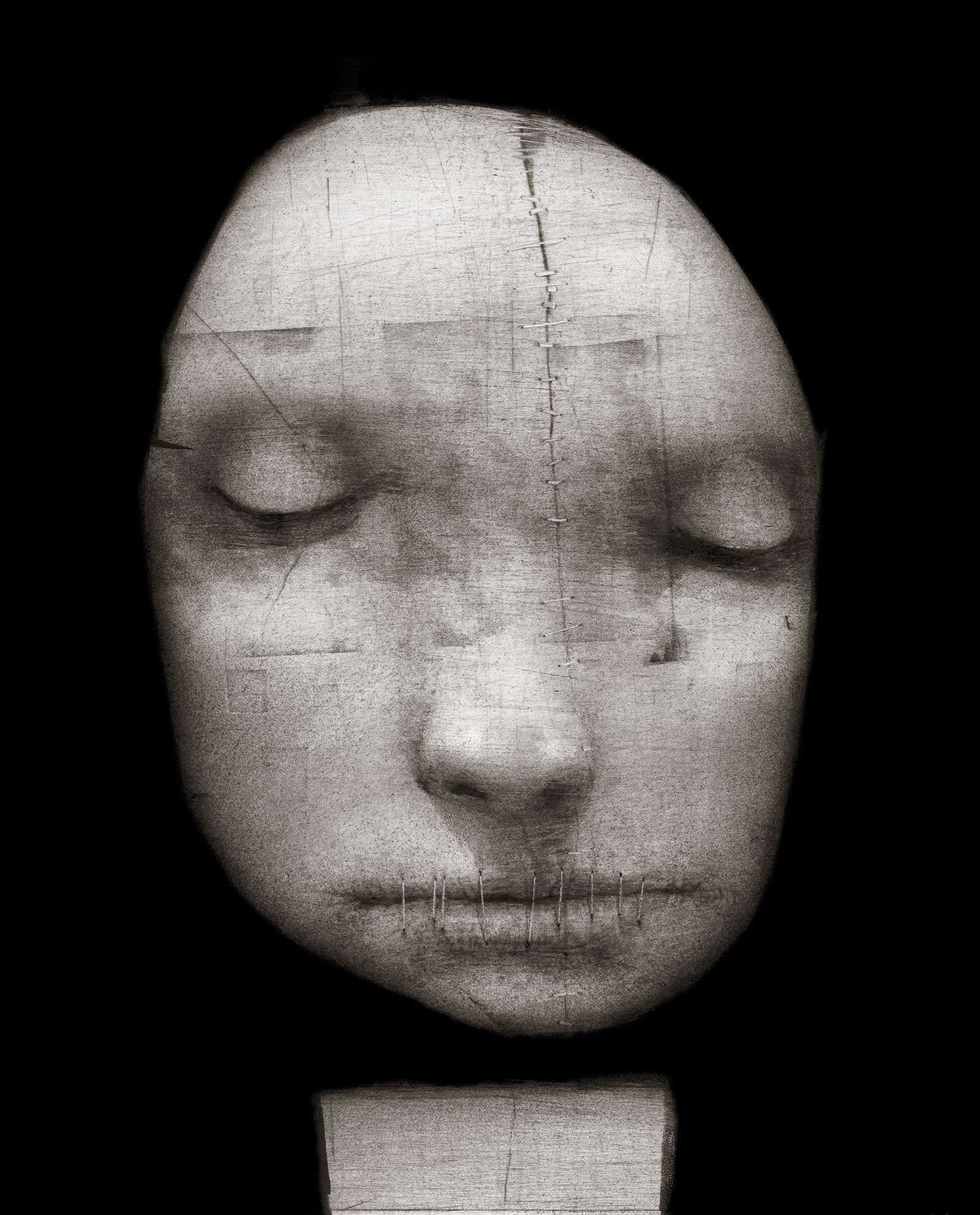

Silence, 1995, monotype with watercolor and black pencil, 14 x 11 in. Courtesy Forum Gallery, New York, NY. © 1995 Alan Magee

Magee moves stones and objects around as a poet moves words around. “Often there is some vague resemblance to a human or animal form, a body, a head,” he says. “In others, there is often a long vertical often resembling an aerial view of prehistoric long barrows.”

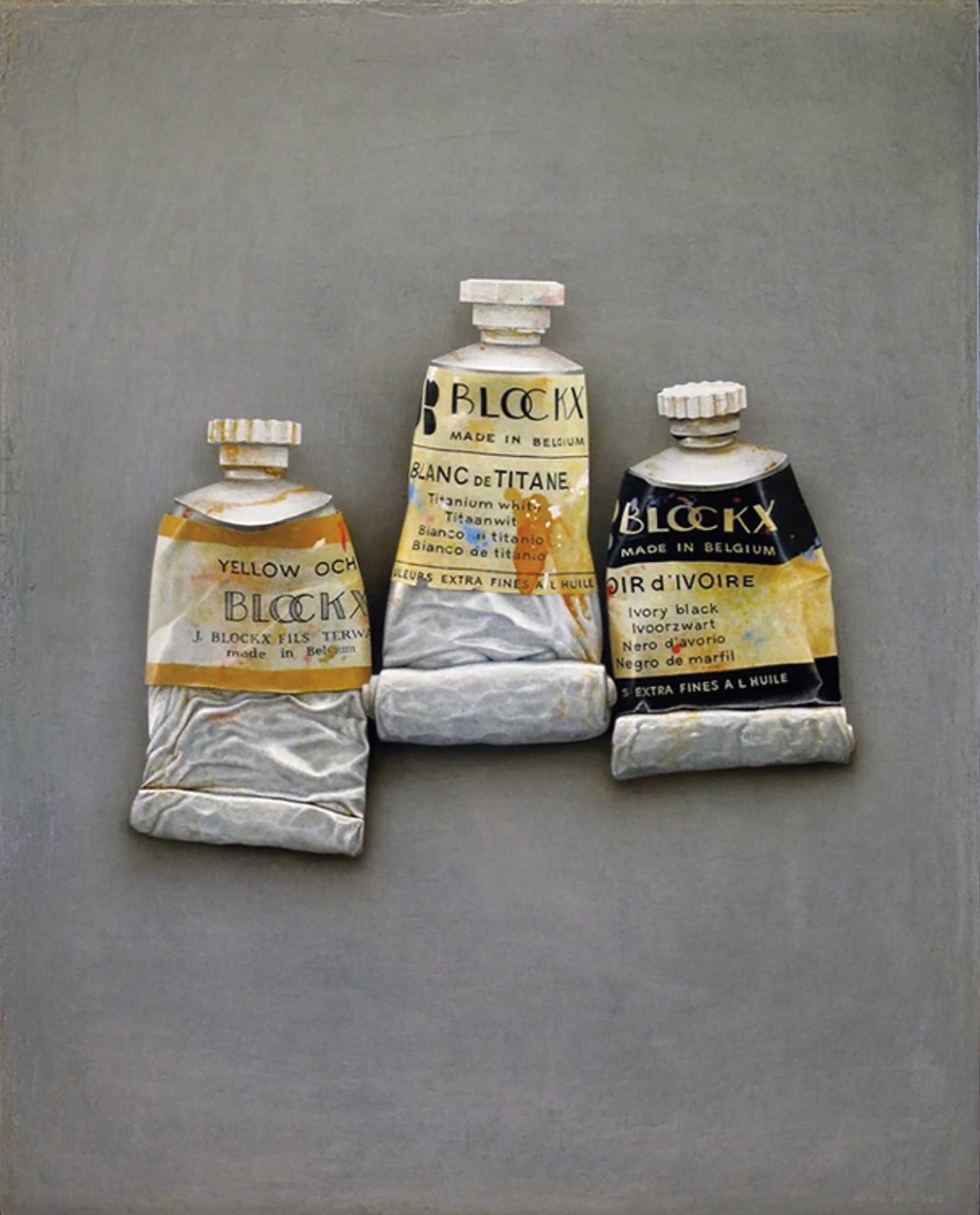

When I told friends I would be talking with and writing about Magee, nearly every one asked, “Does he still paint rocks?” He still paints rocks but also objects in his studio—brushes and paint tubes—well-used tools and historic armor. He makes humanoid sculptures of found objects and, beginning in 1990, a series of monotypes.

Silence, from 1995, is a monotype in a series that he says come from “a product of the late 60s.” The social commentary of Paul Goodman in his book Growing Up Absurdand in the songs of Phil Ochs, the psychology of the Jungian analyst James Hillman, and the essays of Ralph Waldo Emerson about our complicated world, all come into his work.

Surround (for Barry), 2015, acrylic on canvas, 43 x 64 in. Courtesy Winfield Gallery, Carmel, CA; and Forum Gallery, New York, NY. © 2015 Alan Magee

Ochs’ folk music, he says, “affirmed for me an aspect of art where it’s natural to comment on things in society as well as its distressing parts.” The eyes of the visage in Silence are cast down as if in resignation, a skull fracture is randomly sutured and the lips are sewn shut. In the 2019 film Alan Magee: Art is Not a Solace, directed by David Wright and P. David Berez, he sings one of his own songs with Marian Makins. “Singing in the Dark Times” was composed in December 2016, inspired by a metaphor in the poem Motto by Bertolt Brecht: “In the dark times, will there also be singing? Yes, there will be singing about the dark times.”

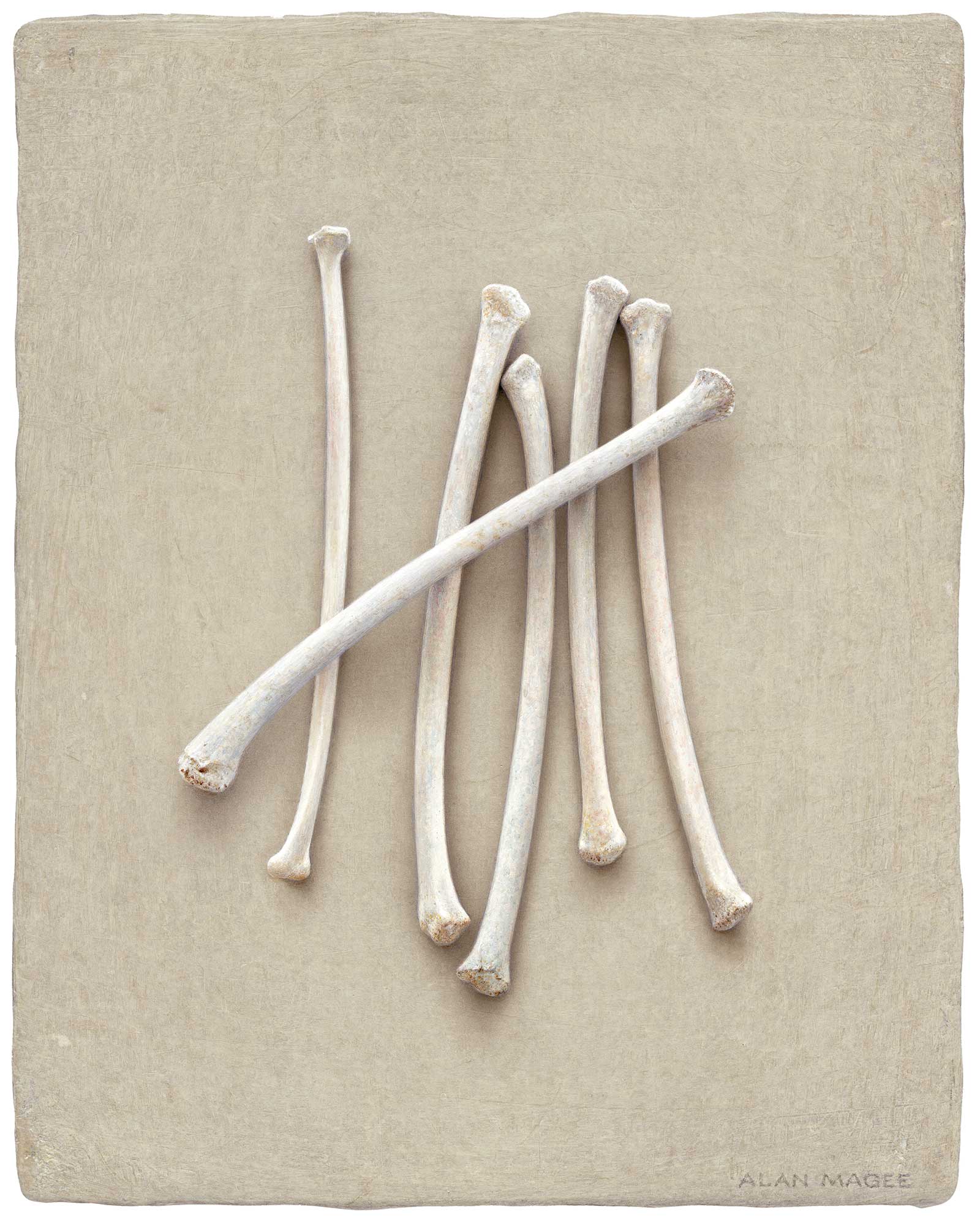

Winter Count, 2016, acrylic on panel, 10 x 8 in. Courtesy Winfield Gallery, Carmel, CA; and Forum Gallery, New York, NY. © 2022 Alan Magee

Ode, 2006, acrylic on panel, 30 x 22 in. Courtesy Winfield Gallery, Carmel, CA; and Forum Gallery, New York, NY. © 2006 Alan Magee

The film opens with the camera moving through an abandoned building, the treads of its stairs worn from repeated use, where enlargements of the monotypes, including Silence, appear as if drawn on the walls, dwarfing their 14 by 11-inch original size. A caption appears, reading, “In the summer of 1990, it became clear that an invasion of Iraq was imminent. Recalling the needless suffering of previous wars, Alan Magee began a new and haunting body of work,” while voiceovers from news broadcasts play in the background. Later in the film, as Magee pushes sticky ink around on a metal plate, a face emerges, to be transferred as a unique image to a sheet of paper. Lopez had written, “Alan is not obsessed with darkness, but he is aware of darkness, and how darkness informs the light.”

Ways of Escape, 2022, acrylic on canvas, 50 x 40 in. Courtesy Winfield Gallery, Carmel, CA; and Forum Gallery, New York, NY. © 2022 Alan Magee

The Irish poet and theologian John O’Donohue wrote, “Take time to see the quiet miracles that seek no attention.” In Ode, 2006, and Ways of Escape, 2022, a wrench and a collection of palette knives celebrate the ordinary. He had seen Sink and Mirror, a 1967 painting by Antonio López García at Staempfli Gallery in New York, which represented his own work. I admired its simple elegance of mundane things on a glass shelf in a white-tiled bathroom several years later when I visited its collectors.

“López García made me want to paint better,” Magee explains. “I wanted to push into another level. It’s not just skill, but quality of mind. Looking at the technical way a painting is done is inescapable. I hope when I paint a wrench or an arrangement of tools, people might stop and see things that are quite beautiful.”

The Winter Months, 2016, acrylic on panel, 40 x 32 in. Courtesy Winfield Gallery, Carmel, CA; and Forum Gallery, New York, NY. © 2022 Alan Magee

The beauty in things that many overlook and the complexity of life that many can’t acknowledge are realities that animate Magee’s work and that of his friend Barry Lopez.

In his book Arctic Dreams Lopez writes, “No culture has yet solved the dilemma each has faced with the growth of a conscious mind: how to live a moral and compassionate existence when one is fully aware of the blood, the horror inherent in all life, when one finds darkness not only in one’s own culture but within oneself. If there is a stage at which an individual life becomes truly adult, it must be when one grasps the irony in its unfolding and accepts responsibility for a life lived in the midst of such paradox. One must live in the middle of contradiction because if all contradiction were eliminated at once life would collapse. There are simply no answers to some of the great pressing questions. You continue to live them out, making your life a worthy expression of a leaning into the light.” —

Powered by Froala Editor