John DeAndrea has never been sure he’s an artist but his sculptures and those of his late friend Duane Hanson, have captivated the art world for decades. I once crossed in front of a person seemingly contemplating a painting on the opposite wall of the Institute of Contemporary Art in Boston and said, “Excuse me!” A few seconds later I realized, mortified, that the “person” was a Duane Hanson sculpture—cast in fiberglass and wearing actual clothing. DeAndrea’s sculptures are, primarily, nude and unlike the idealized figures of classical sculpture, bear the pores and scars of the models from whom they were cast—disquietingly “real.”

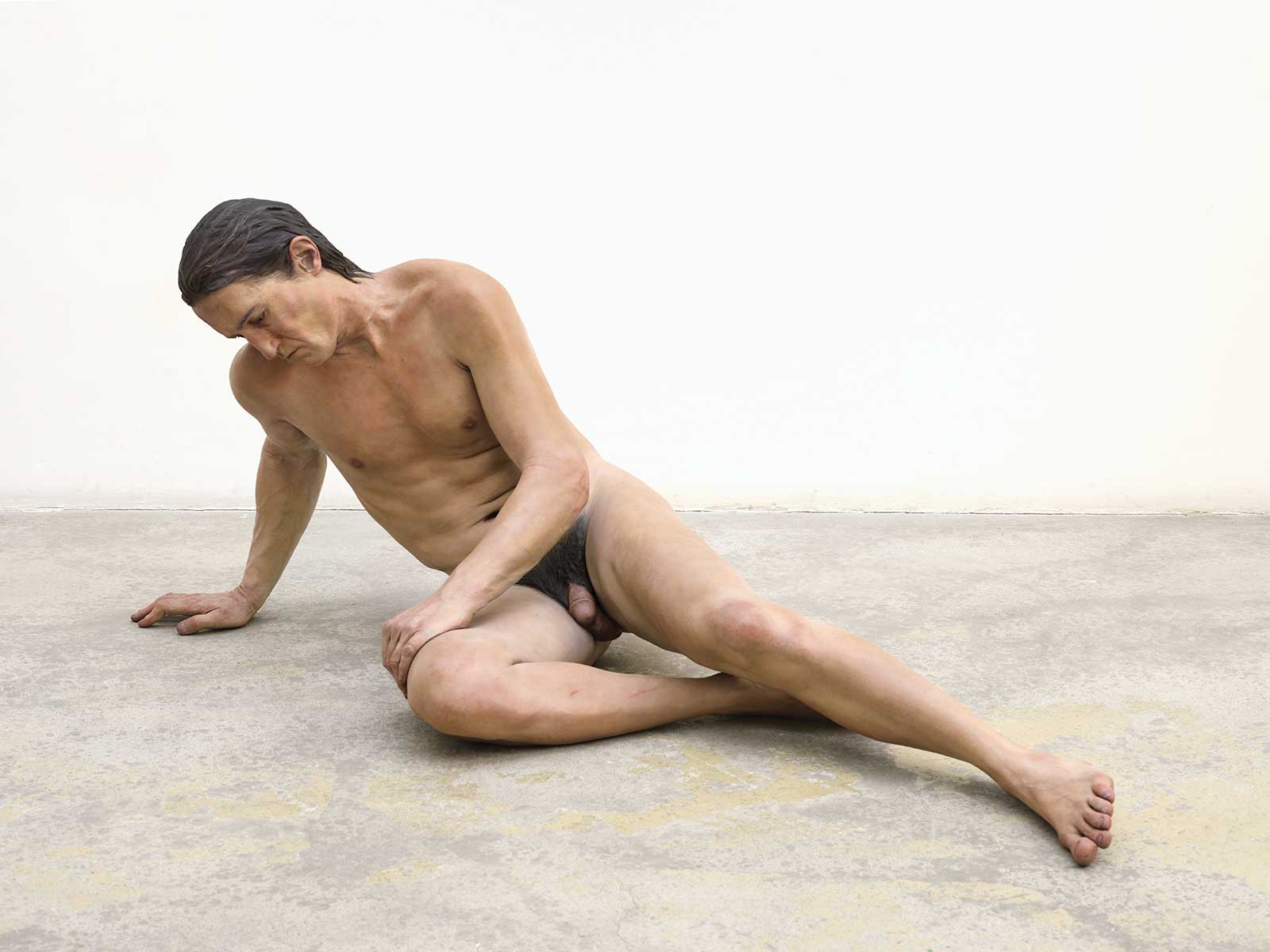

Dying Gaul, 2010, polychrome bronze, glass eyes, 26 x 65 x 25". Courtesy Galerie Georges-Philippe & Nathalie Vallois, Paris, France. Photo: Clérin-Morin.

Both DeAndrea and Hanson first showed their work in the early 1970s at Ivan Karp’s new OK Harris Works of Art in New York, one of the first galleries in SoHo. At that time neither was famous, nor was Karp. The New York Times would call Karp “New York’s deftest and most enthusiastic salesman of the new art.” His gallery showed not only the two young realist sculptors but the best photorealist painters, as well as Andy Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein and Robert Rauschenberg.

DeAndrea had sent slides of his work to galleries in New York receiving in reply either a resounding “No!” or nothing at all. Karp kept his and other artists’ slides and used them in lectures. Karp, however, sent a hand-written note when he was opening his gallery saying, “Send me the sculptures. If they talk to me, I’ll sell them.” He sold the first sculpture for $800 to an important German collector and dealer and sent the entire amount to the artist, knowing he was broke.

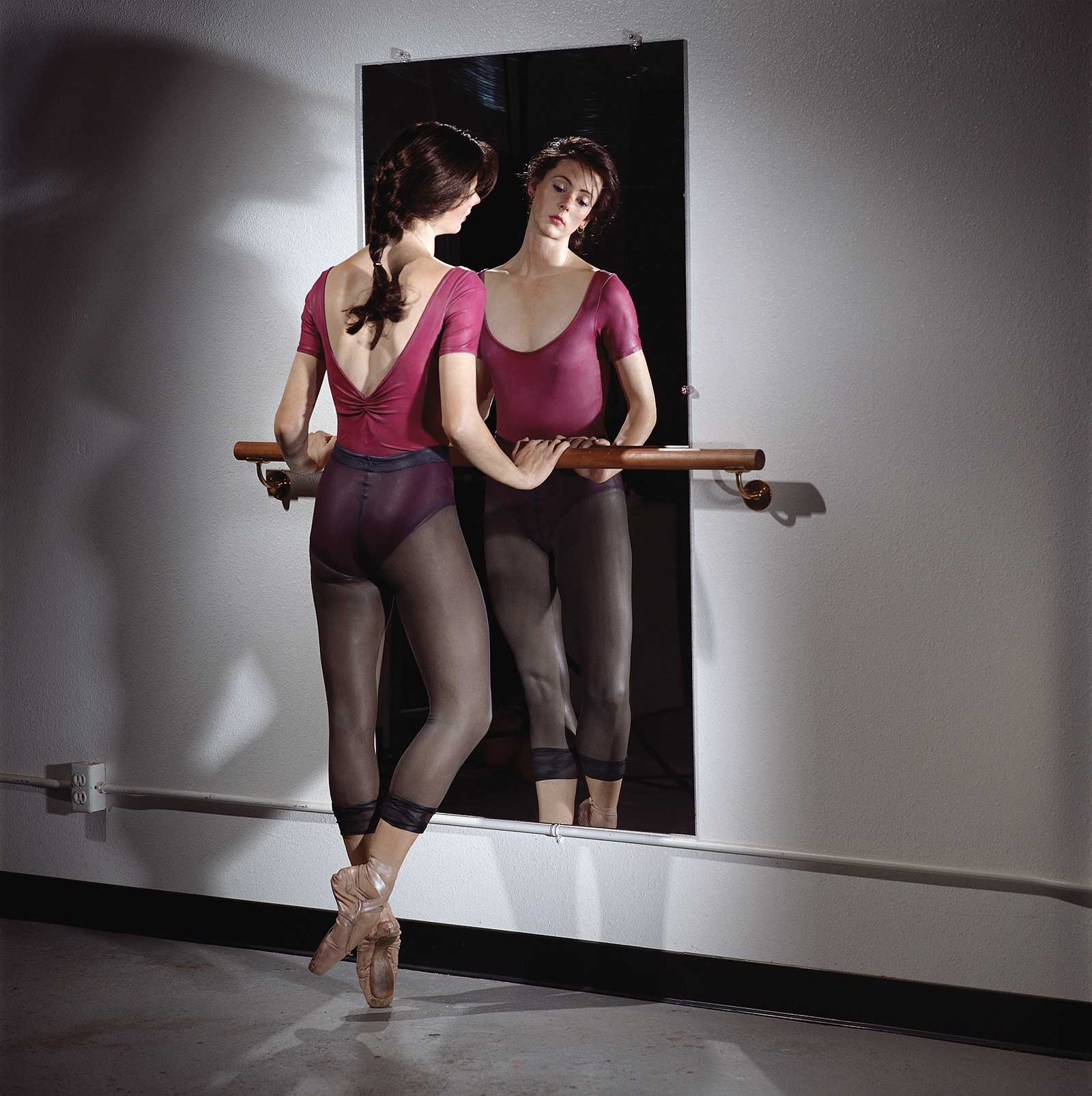

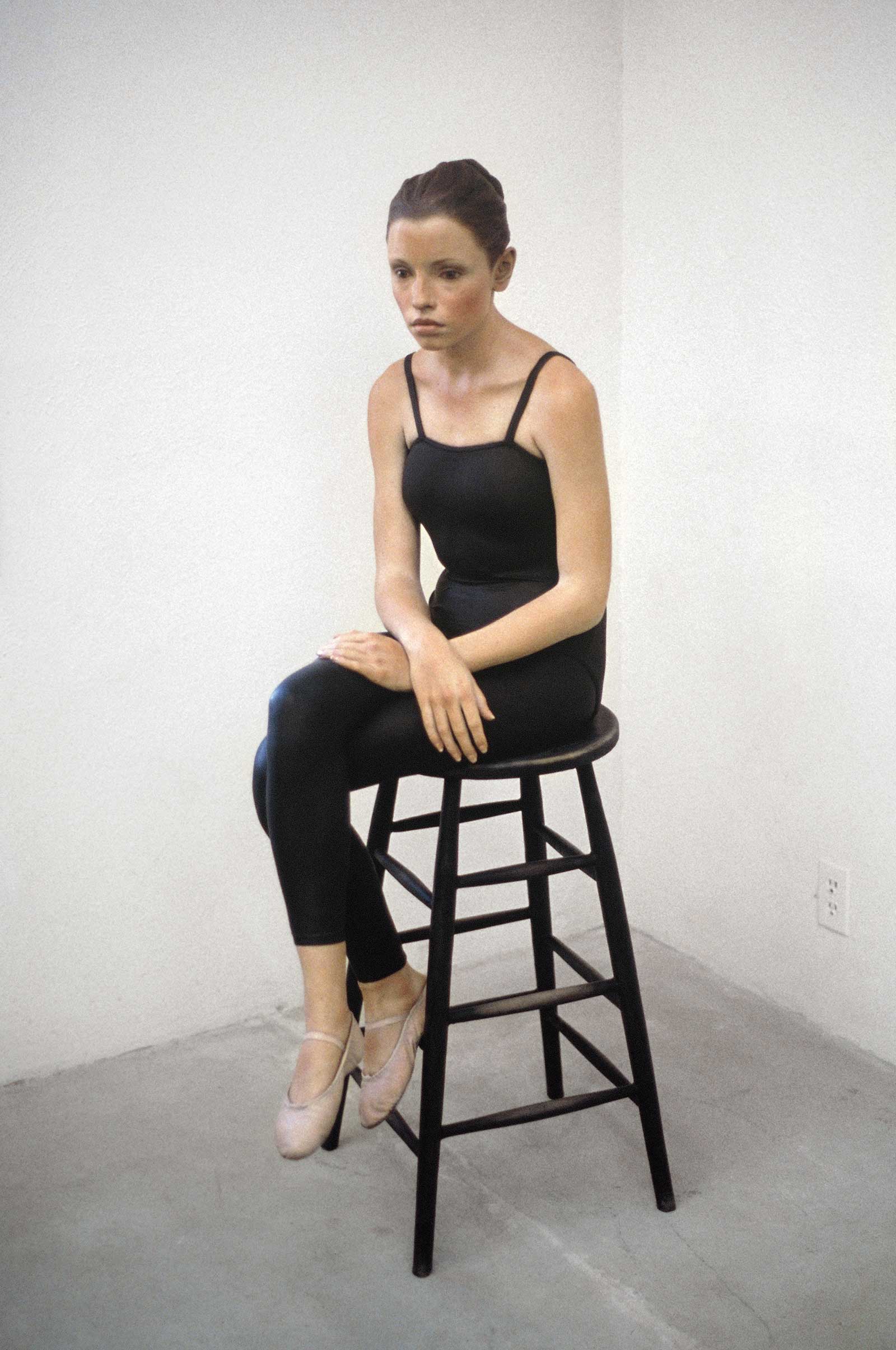

Ballet Dancer, 1993, polychromed polyvinyl and mixed media, lifesize. Private Collection. Courtesy of artist.

“I had been cleaning a bar starting at 2 in the morning, seven days a week for five years," shares DeAndrea. The bar was his father’s which he always referred to as ‘the joint.’ In his autobiography, written with Elaine Eldridge, DeAndrea explains, “I quit my job at the joint the same day I got the $800. I’d been clearing $57 for a seven-night week. I never had a regular job after that. It was magical. I didn’t understand what was happening. Other artists talked about what their work meant, which seemed like a luxury. I didn’t know what my work meant. I wasn’t even sure I was making sculptures. I just made them. Later on they were sculptures, but not in 1968, ’69. I kept making them. For 40 years I did that. I didn’t talk about my work. In my studio I was an artist, but when I wasn’t in my studio, I was just an average Joe, riding my motorcycle, getting drunk with my friends.”

Clothed Artist and Model, 1976, polychromed polyvinyl and mixed media, lifesize. Private Collection. Photo: D. James Dee. Courtesy of artist.

In an oral history interview with Duane Hanson in August of 1989 for the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art, Hanson described himself and DeAndrea as artists: “I am what I am as an individual artist. I think I’m different from photorealists and a wonderful artist like John DeAndrea who does very classical, hyperrealistic, beautiful nude figures. Sometimes they confuse us, the public. I don’t know why because we’re miles apart. I know John. I admire him and I’m sure he admires me in different ways. We work differently; our techniques are similar. We use similar materials, but he’s into a rather aesthetic statement of a beautiful-bodied person, and there’s nothing wrong with that. I’m interested in—I don’t know. I see beauty in the fat ones, and lean ones, and the ugly ones. I hate the word ‘fat’ and ‘ugly’ because I think a human being is beauty and it’s truth.”

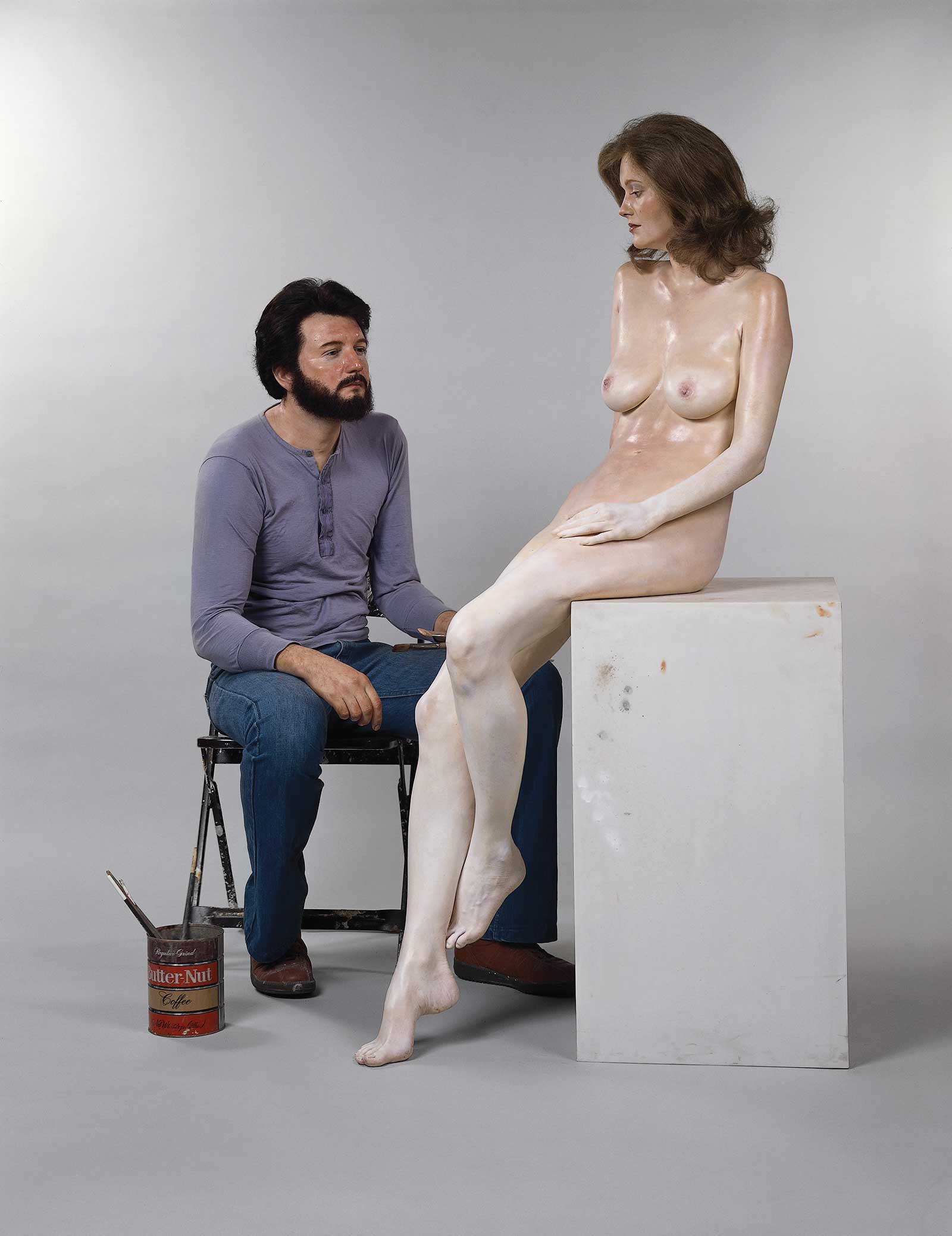

Self-Portrait with Sculpture,1980, polychromed polyvinyl and mixed media, lifesize. Private Collection. Photograph by Gary Sinic. Courtesy of artist and Louis K. Meisel Gallery, New York, NY.

I admired DeAndrea’s willingness, even at 83, to say “I don’t know” when we talked about his sculptures. There are amusing stories about learning about fiberglass from a kayak maker when he was studying in Albuquerque, and promising the models that the molds wouldn’t stick to their bodies or hair and then they did, and he had to learn how to prevent that from happening in the future. “It took a long time to figure out, how to get it right,” he says. “I threw away tons of molds.

“I had no interest in modeling the figure in clay, for instance. I was after something else. I had to have a mold of a person, people who appealed to me, who had a personality. That’s another thing. I didn’t go for real beauties. My models have been people I met and knew. It made it easier for them to relax and not to ‘model,’ and get to a natural pose.”

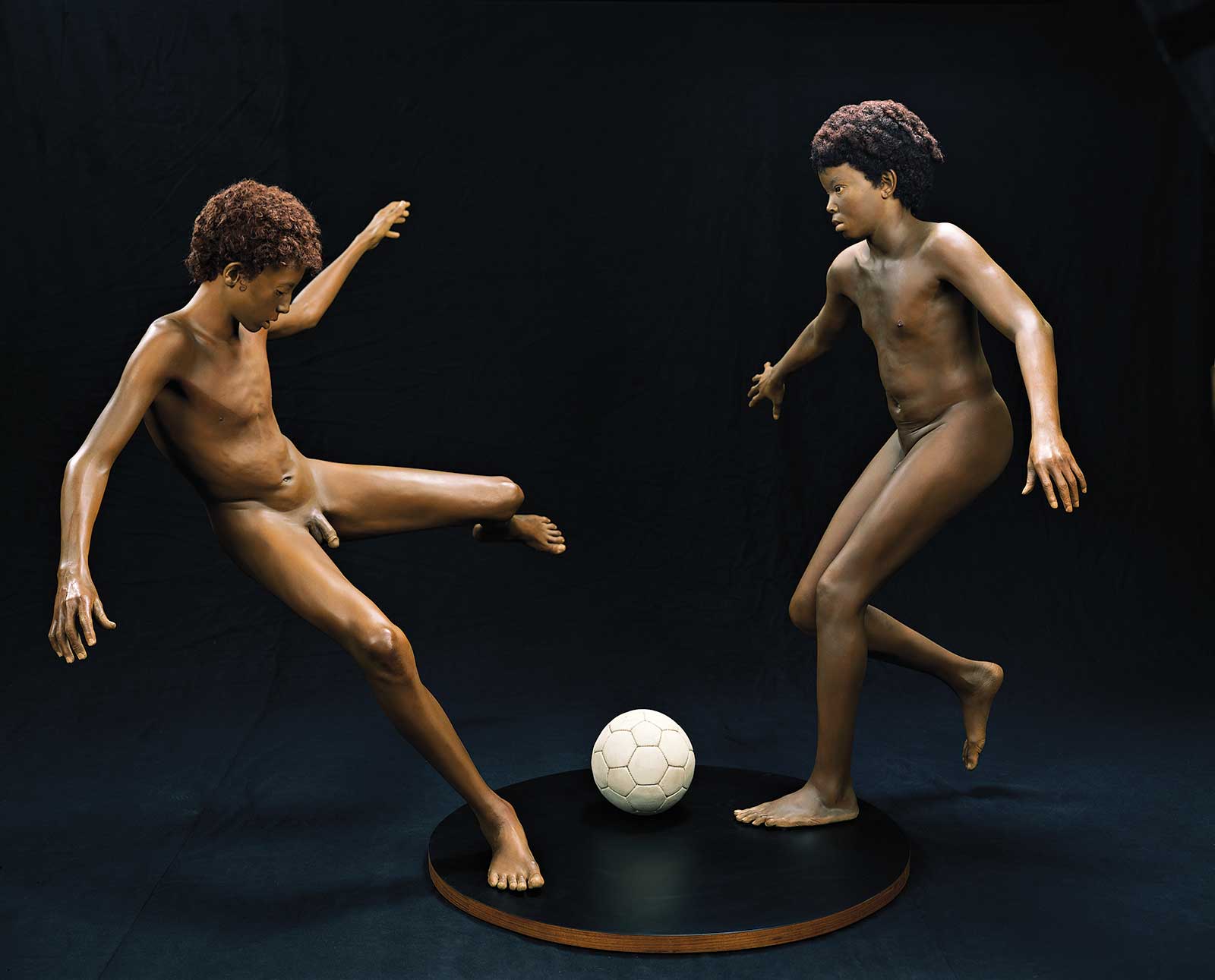

Boys Playing Soccer,1971, fiberglass, polyester and mixed media, lifesize. Collection of the Everson Museum of Art, Syracuse, NY. Courtesy of Artist and Louis K. Meisel Gallery, New York, NY.

DeAndrea often mentions the “magic” of creating his sculptures. “A creative magic hits a young man and he doesn’t know why he does what he does. He just does it. Bob Dylan had the answer to my doing my stuff. When he was asked about his early songs he said, ‘I don’t know how I got to write those songs. Those early songs were almost magically written.’

“It happens in art all the time. Michelangelo did the Pietà and David when he was in his 20s. Picasso began his Blue Period when he was 20. I don’t know why this happens. They’re not smarter. The magic comes from nobody knows where. When I did my sculptures, I didn’t know what I was doing but I had to make the figure talk to me.”

Sometimes it takes the right model for his vision of a sculpture to be realized. “I had been wanting to do a Dying Gaul.I looked at people for 40 years until I found the right person in my wife Lorraine’s brother.”

Adam & Eve, 2021, polychrome bronze, glass eyes, acrylic hair, Adam: 67 x 19¼ x 17¾", Eve: 63 x 15¾ x 11¾". Collection Fenix Museum, Rotterdam, Netherlands; Courtesy Galerie Georges-Philippe & Nathalie Vallois, Paris, France. Photo: Clérin-Morin.

The classical Dying Gaul is a Roman marble copy of a Hellenistic Greek sculpture. Although realistic, it is idealized. DeAndrea’s Dying Gaul, 2010, with its stylish hair and cropped beard and the intimate details of his body is more real and may suggest a more contemporary, more personal defeat.

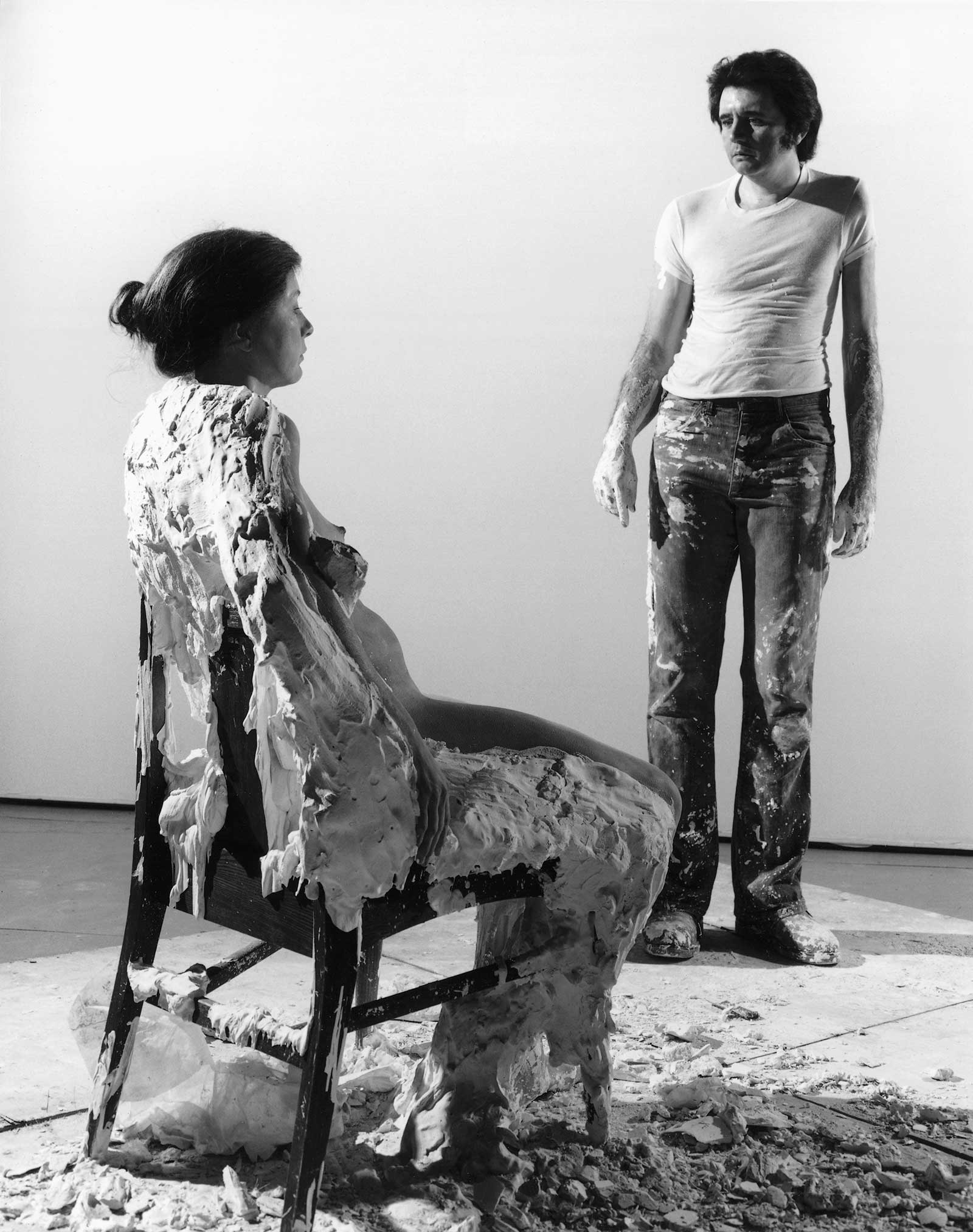

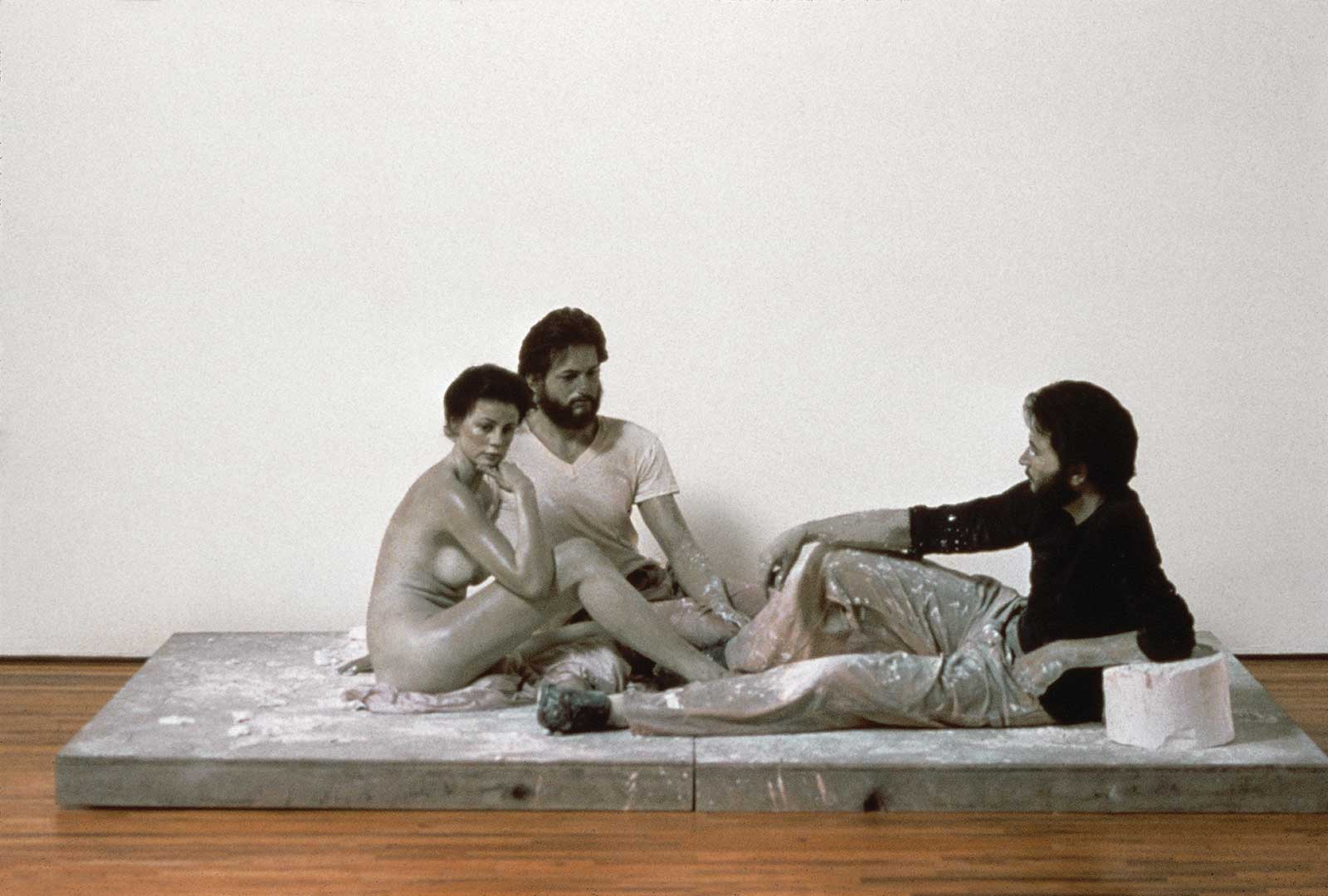

DeAndrea celebrates his process in other references to historic art. Manet: Le Déjeuner sur l’Herbe, 1982, depicts the two clothed males and the nude female of Manet’s painting in three dimensions—the female sleek with Vaseline for the plaster casting and the artist splattered with plaster.

In Self-Portrait with Sculpture, 1980, the artist brings the sculpture to life as he applies paint to the figure. The scene is reminiscent of the story of Pygmalion and his sculpture Galatea with which he fell in love. The attitude of DeAndrea in his sculpture appears to be one of making the sculpture as lifelike as possible, charged with life rather than erotic tension.

Tara, 2000, ed. of 4, painted bronze with mixed media, lifesize. Private Collection. Courtesy of artist.

In a 2023 exhibition, Ceci n’est pas un corps, at the Musée Maillol in Paris, the museum noted, “Over the course of 50 years and 350 sculptures, DeAndrea has refined his technique to capture the human spirit.” The title of the exhibition is a play on the title of a painting by René Magritte—Ceci n’est pas un pipe (This is not a pipe). The museum continues, “The exhibition presents a series of sculptures which challenge our understanding and perceptions of art. Reality, art or copy? Hyperrealistic artists turn their backs on abstraction and look instead to achieve a meticulously rendered representation of nature to the point where the spectator is sometimes left wondering whether they are in fact dealing with the living figure. These works therefore often evoke a feeling of strangeness or uncanny, but always carry meaning.”

Ariel I, Ariel II, Ariel III (three separate works; same model), ed. of 4, 2011, painted bronze with mixed media, lifesize. Private Collection. Courtesy of Artist and Louis K. Meisel Gallery, New York, NY.

DeAndrea might be at a loss to explain the meaning of his sculptures but their purpose is always to be objects of beauty. “Originally, I didn’t know much about realism,” he says. “I wanted to make them more beautiful than anything. I want them to speak to you.”

When I asked him what of himself is in his sculptures he immediately replied, “Oh, boy, am I in there.” He had polio when he was 8 and was left with a nearly useless left arm and hand. He comments in his autobiography, “When I look at pictures of some of the statues I made, like Boys Playing Soccer and Susan, I think, ‘How in the world could I do that?’ Doing what I did with one arm was impossible. But I did it.”

Brunette with Drape, 1983, recast in 1998, polychromed polyvinyl and mixed media, lifesize Private Collection. Courtesy of artist. Photo: Jon Abbott.

He has also dealt with effects of sexual abuse by a female housekeeper that began when he was 6, as well as violent physical abuse by his alcoholic father. In 2006 he had an abscessed tooth removed. He wasn’t given enough antibiotic to stop the infection and it traveled to his brain where it formed another abscess, the effects of which were similar to a stroke and resulted in paralysis on his right side. He says, with a touch of humor, “You’d think it could have taken the polio side, wouldn’t you? Nope.”

Manet: Le Déjeuner sur l’Herbe, 1982, polychromed polyvinyl and mixed media, lifesize. Collection of the Speed Art Museum, Louisville, KY. Courtesy of artist and Louis K. Meisel Gallery, New York, NY.

He says his models and his own personality are in his sculptures. “They’re physically beautiful people. I always wanted to be beautiful. You have polio as a little boy and you’re never a whole person. I couldn’t be the person I was going to be. I had polio and was not complete, but I could make the figures complete. I made them like I would like to be.” —

Powered by Froala Editor